6:4

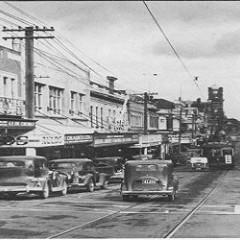

Bitter controversy followed a suggestion that the tram to Vogeltown should be routed through Pukekura Park. The tramlines were extended up Liardet Street to the park gates, with a branch line running a short distance to the west along Gilbert Street, but this proved uneconomic and the Liardet Street lines were taken up in 1937. During the Second World War, when many motormen and conductors were called up, conductresses were employed. On January 27, 1948, the borough council decided to install a trolley bus service on part of the tram routes. Five years later the trams were taken offthe service, the tram lines were removed and diesel buses (the first having been bought in 1938) took over on Friday, July 23, 1954. It was a gala occasion. More than 3000 citizens thronged Devon Street to farewell the trams. Many people didn't want to see them go, and dance floor powder and grease were spread on the rails on the slopes. But plenty of sand was available, and the trams, all of which gave free rides to all who wished, made the grade. As the last ageing vehicle crept home, with warning bells clanging, staff at the power substation threw switches, halting the vehicles several times. The trams were richly decorated for their last ride. 'You'll never miss me again', 'You heard me coming, but you'll never smell me going', and 'I've been rubbered' were some of the slogans painted on their sides. The first trolley buses started operation in October, 1950, and for 17 years (their life expectancy was originally estimated at 15 years) they gave efficient and comparatively silent service for more than 2 million kilometres, carrying more than half a million passengers. When they were discontinued in favour of new , powerful diesel buses on October 7, 1967, it, too, was a gala occasion. A Taranaki Herald reporter wrote: 'For several years I have been a frequent traveller on our trolley buses and in common with many hundreds of satisfied customers I watched with sadness this morning's valedictory procession. Like three f~ded, elderly but still proud old ladies (the fourth had been an invalid for more than a year and was still in hospital) they trundled silently on their last journey, followed by the gleaming juggernauts who will take over from them. The only noises they made was creaking of their ageing bodies as they laboured up Morley Street. In all the years I have used them I can't recall having heard any of them sound their horns in anger-or indeed any other emotion. I didn't even realise they were equipped with horns. But as the last of the three old ladies rounded the Liardet Street corner there came from deep inside her, as though it had difficulty in emerging, a sound quite unlike anything I have ever heard: a cracked, wobbly, feeble noise; not angry, not rejoicing, but rather protesting. She kept it up until it was drowned in the purposeful rumbling of the diesel monster which followed her. I felt I should have raised my hat.' The trolley buses were sold to the Wellington Transport Museum, and at a ceremony when Mayor A. G. Honnor declared their services ended,

the president of the museum, Ian Little, handed over a cheque for $12,000 to K. R. B. Waite, chairman of the city council's transport committee. Diesel buses have taken over the council's public transport business since that time. By 1979 statistics revealed their value was $2,400,000; they serviced 45km of city routes-and they ran at a loss of $238,000.

Geographically, New Plymouth is out on a limb; a terminus. Unlike most other cities of comparable size, travellers don't go through New Plymouth to get somewhere else, unless they go out of their way to do so, although for some years it was a link in the road-sea chain between Auckland and Wellington. Efforts of early local bodies, continually prodded by the settlers, to obtain easier access to the 'outside world' than that allowed by ancient Maori tracks, passable only by horse or on foot, were comparatively slow in bearing fruit. The first coach, a horse-drawn four-in-hand, arrived in New Plymouth on January 12, 1871, from Wanganui via Hawera and Opunake. After a most arduous trip, five hours behind schedule, it was welcomed late at night by riotous crowds. 'Bunting was floating in the wind from all parts of the town,' said the Herald. Driven by coachmen W. H. Shepherd and A. Young, it belonged to Cobb and Co., which had been awarded a contract to deliver mails and passengers twice weekly each way between Wanganui and New Plymouth for $6000 a year. One of the passengers on that first trip was Prime Minister William Fox, who was so exhausted that he was unable tojoin in the town's celebration with the drivers and other passengers. On the first anniversary of the service the Taranaki Herald reported that it 'continued to run with surprising regularity' in spite of the vagaries of Taranaki weather, which frequently turned such roads as existed into seas of mud and made many fords impassable. 'Through' passengers could take ship to Auckland after braving embarkation on vessels anchored in the roadstead. One of the best remembered drivers of the 1870s was Frank Emerson, who was 'most experienced, picking the smoother parts of the track so as to render coach passengers comfortable passage'16 and who acted as a tourist guide, indicating points of interest such as the wrecks of the Harriet (offWaitotarainI834) the Lord Worsley (Namu Bay 1862)and the Marchioness (Warea 1864), all of which were partly visible in the surf. The coach services (there was a twice-weekly run to Waitara) resulted in an increase in the number oflivery and bait establishments in the town and ranks of hansom cabs, broughams and gigs lined up outside the White Hart Hotel, the 'coach terminus', to convey passengers to their destinations in and out of the town. For more than 30 years this was the transport pattern. The more enterprising tradesmen used horses and buggies to deliver groceries and

drapery, furniture and parcels to settlers in the town and on nearby farms. One of the town's grocery shops, at the corner of Dawson and Morley Streets, was owned by Frederick Hill (who later became a borough councillor). In 1907 he bought a motor delivery van and employed young George Gibson as his driver. For seven years George delivered to customers as far away as Waitara and Omata, and the van became a familiar and welcome sight. In 1914 Gibson decided to enlarge his field of endeavour. He bought a second-hand Overland touring car and set up business as a taxi driver, with headquarters in the then recently vacated two-storey wooden fire station in Powderham Street. Here he and his sole competitor, Bill Ward, who owned a Daimler tourer, shared the use of garage and workshop space, with Mrs Gibson taking messages for both of them. Each called on the other when demands exceed their individual resources. In spite of competition with horse-drawn cabs and hackney carriages, business thrived and in 1916 Gibson bought two new Buick cars. Petrol cost 9c a gallon in cases containing four-gallon tins. Unsealed roads were very hard on tyres, vehicles and drivers, and soon Bill Ward pulled out of the business. Gibson increased his fleet of Buick taxis to six and later bought out Snelling and Andrews who ran seven-seater Hudson service cars between New Plymouth and Opunake. In 1922 Gibson decided to enlarge his business. He affiliated with White Star Transport and formed the company of Gibson's Motors Ltd (later Gibsons Coachlines) a firm which for the next 57 years built up a reputation for courtesy and service on the New Plymouth to Auckland run. In 1979 the firm was taken over by Newman's Coachlines. New Zealand Railways ventured into road services in Taranaki when it bought the passenger service between Wanganui and New Plymouth from Hodson's Motor Service Ltd in 1940 and the following year began regular services to Wellington as well as a rail-road link with Gisborne. As with so many other innovations, the railway was late in coming to New Plymouth. The country's first steam locomotive railway was opened on December 1, 1863, and ran over a 6 km track between Christchurch and the temporary port at Riverport. It was not until 1875 that Taranaki's first railway line was opened-the 18 km stretch between New Plymouth and Waitara. Laying this line was no mean achievement. Octavius Carrington surveyed the route. Work began in 1873 and the line was opened on October 14, 1875, by Miss Jane Carrington breaking a bottle of champagne over the locomotive Fox, named in honour of the Prime Minister."? There were problems: 'Owing to insufficient power in the locomotive the engine was dead beat in bringing excursionists from Waitara and numbers of passengers had to alight and assist in getting the train up the Waiongona Hill,' said a reporter who travelled on the first journey.

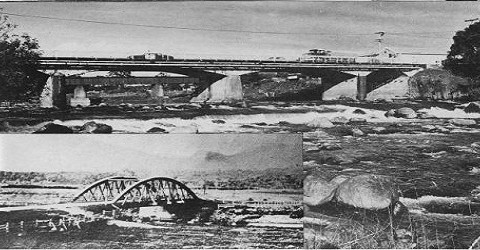

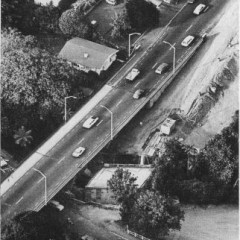

In spite of many efforts to have the line extended (the Waitara-New Plymouth route was planned as the first part of a line intended later to reach Wanganui) it was many years before this came about. Inglewood was linked by 1877, Stratford in 1879, Hawera in 1881 and Wellington in 1886. It was not until 1932 that the line between Stratford and Taumarunui enabled Taranaki people to travel to Auckland by rail. The original line of the railway through the town left the station, followed the western bank of the Huatoki to cross Devon Street, then curved to cross Carrington Street over a trestle bridge a few metres to the south of the present one-way Vivian Street road bridge, along Leach Street to meet the present route alongside Waiwaka Terrace. It was not long before the street crossings posed problems; a by-law was passed regulating horse traffic over the Devon Street line which was considered to be a possible death trap, and train speeds were limited to 7 km an hour. Indeed, these fears were justified and after several deaths (including four in one year, 1901, one of which was former Superintendent Charles Brown) the line was re-routed in 1907 to its present position. This robbed the town of a potential marine parade, for the line to the port had been extended in 1885. For more than a century the railway has brought great benefit to the town, but at considerable cost. The historic hill, formerly the Maori pa Pukeariki and later named after Lord Eliot, a member of the Plymouth Company, was over the years levelled; to be used in reclamation of the land on which the station now stands; the pleasant park-like appearance of the area round the Huatoki River mouth was buried under rail marshalling yards. Some relief may be expected when the move of the yards to the Smart Road area takes place in the 1980s, but the steel lines will still hinder access to the seafront. Next to the railways, the most important step in the development of communications was the establishment of a port for the town. After more than 40 years of agitation, enthusiasm, opposition and vacillation, the first positive steps were taken in 1875 when a harbour board was constituted, with F. A. Carrington as its chairman, and in which was vested a quarter of the revenue gained from the sale of Crown lands in Taranaki. Plans were prepared and on receiving the Government's approval in August, 1879, construction was begun on a breakwater near the Sugar Loaves, using rock from Paritutu.!? Unfortunately this material proved unsuitable and new plans had to be made for the breakwater, using concrete blocks. Fresh approval was given by the Government in August, 1880, and on February 7, 1881,40 years after selecting the site of the town, Carrington laid the foundation stone of the breakwater. In addition to being the culmination of three years of 'local and provincial jealousies, of muddled finances, of narrow and selfish interests those attending any comparable undertaking in the Dominion