1

X MARKS THE SPOT

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 brought peace to a Europe torn by two decades of debilitating wars. For the common man, however, peace did not bring prosperity; but it did result in a rapid population increase which, in Great Britain, began to pose grave problems. As after former-and later-wars, the drop in demand for war materials was severely felt and it took trade and industry a long time to adjust to the different needs of a post-war nation. Heavy unemployment, a succes- sion of bad harvests and worse winters resulted in famine or at least in near-starvation for many.

It was natural that those hardest hit should have seen emigration as a solution to their plight. The temperate regions of the world beckoned. Captain James Cook had taken possession of Eastern Australia in 1770 (during the same series of voyages onwhich he had circumnavigated New Zealand). His reports to the British Government were timely and were given close study by a nation plagued by a problem to which there seemed no solution. Why not make Australia a vast prison? For many years America had served this purpose, but since the War ofIndependence this avenue was closed, and men, women and children 'criminals' were dying of disease and starvation in over-crowded, rotting and foul prisons in London. Thus, from 1788 until 1840, thousands of convicts were sent to Botany Bay and Port Jackson, to be conveniently forgotten by the British Government. This was the start of Australian colonization.

Not so in New Zealand. Soon after Cook's discovery a small English community-mostly whalers, sealers, shipwrecked mariners and a few escaped convicts from across the Tasman-was formed in the Bay of Islands. Tolerated by the Maoris, to whom they introduced firearms, liquor and previously unknown diseases, they posed a threat to the Maori way of life. When the Rev. Samuel Marsden established his mission in the Bay in 1814, he was shocked at the damage these' ruffians' were inflicting. He and other spreaders of the Gospel strongly opposed any moves to colonise the country. For a time they were successful, but soon other areas of New Zealand were being 'discovered' by whalers and traders. One of these was Dicky Barrett. An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand refers at some length to 'Barrett, Richard (1807-47), Wellington pioneer' as being intimately associated with the earliest history of Wellington, which indeed he was. It refers to his 'active involvement in the internecine wars between Taranaki and Waikato Maoris' and the rest of the biography concerns his activities in the Marlborough Sounds and Wellington. 'His death at the age of forty was widely mourned.

He was a force to be reckoned with in the early days of colonisation of the capital. ' It does not say where or how Barrett died, or where he was buried. The Wahitapu Cemetery off lower Bayly Road in New Plymouth, neglected for many years, marks the burial place of a number of Maoris and early European settlers. Prominent among the head-stones is one marking the grave of Barrett, his wife and their eight-year-old daughter. Barrett was much more than a 'Wellington pioneer'. Early historians have recorded his life in some detail and have variously given him credit for being 'a highly qualified interpreter and pilot";' 'no ordinary man";? 'that highly inadequate interpreter'; 3' an adventurer, tough ignorant and unscrupulous";" and 'the feelings of the best lady in the land would not be shocked by his language, not even a word he would utter or a look he might give".' But many writers refer to him with more than a hint of patronage, probably because he was a common whaler, a trader who had 'gone native'. It should be remembered, however, that he was a leader in a 'rough community ruled by a few men of iron will and large limb whether in a whale boat or in a fight on shore, some few too, though very few, like Barrett, were respected for their kind-hearted ness to all.

A few hundred metres to the west of the Wahitapu Cemetery there is another monument, well-cared for in its lawn-surrounded tree-studded piece of level ground. It stands on a promontory and bears the names of the ships which brought Taranaki's 'first settlers' between March 31, 1841, and June 23, 1843. History regards Frederic Alonzo Carrington, who had arrived in the country in the barque Brougham in 1840, as the 'Father of New Plymouth', because, as a surveyor commissioned by the New Zealand Company in England, his task was to choose and mark out a site for the New Plymouth settlement. In effect, settlement had begun, though not officially, 13 years previously when Barrett set up a whaling station and trading post at Ngamotu in 1828, and the 'first settlers' were very grateful for his help and hospitality on their arrival, and afterwards. It is doubtful, indeed, if settlement could have proceeded as comparatively smoothly as it did, had it not been for Barrett's presence. Carrington and Barrett were opposites in almost all respects. Neither was a member of the' upper classes'.

The former was the son of an army captain, of Chelmsforth, Essex; Barrett's origin is uncertain but it is popularly supposed he was born in Yorkshire and although Scholefield' s Dictionary of New Zealand Biography sets his birthplace in Rotherhithe, London, the Mayor of Bermondsey, Alderman J. Mahoney, says there is no mention of the birth in any of the area's parochial records. Carrington, who trained as a civil engineer, was 'a fastidious man and it was this quality that made him such a good technician and surveyor and draughtsman'. 7 The two men were experts in their own fields: Carrington, meticulous and methodical in everything he did, was a gentle man, kind to those he regarded as inferiors, critical of his employers where he felt it was necessary; a man who did not suffer fools gladly. Indeed, it was his stand against some of the country's early administrators which resulted in him being 'hounded out of the Colony' in 1843.8 Barrett had relied on the strength of his character-and his arm-to become a leader in an extremely hard school. When the Tory bearing the first official colonis- ers, arrived in the Marlborough Sounds in August, 1839, he was able to counsel them-and later Carrington-on the way of the Maori in a manner few other men could. Barrett was by no means the first European to sight Taranaki and its mountain. The Dutch captain, Abel Tasman, reported having seen Mount Egmont on November 27, 1642. In January, 1770, Cook saw 'a very high mountain' which he named Egrnont ' in honourofthe Earl' and 'there were some very remarkable peaked islands' (the Sugar Loaves)." In 1817 the American brig Agnes was seized by Maoris while lying at anchor in Poverty Bay and all the ship'scompanyof15, except an Englishman, John Rutherford, was killed. Rutherford was given two daughters of the local chief. 'The Englishman did not object to the plurality. '10 Made a chief, he came overland to Ngamotu with a party in 1817 where he met a fellow countryman, James Mowry, also the survivor of a ship's crew's massacre, and who had taken as a wife the only daughter of the chief who had saved him.

A Sydney trader, John Marmon, said in a narrative of his life that he visited Taranaki in 1824 in the schooner Henrietta to buy flax from the Maoris. 'When we landed there were at least two thousand natives assembled, all of whom were very friendly.'

Other traders and whalers may have landed at Ngamotu during the early part of the 19th century, but the first' official' recorded history of Europeans coming ashore dates from the loss of the trading vessel Adventure which sailed from Sydney on May 29, 1828, bound for Taranaki.'? She was commanded by John Agar Love, a Scot, with Barrett as mate. On her arrival later that year the little ship anchored off Ngamotu and all her crew, with one exception, came ashore. During the night a heavy gale sprang up, the vessel parted her cable and was driven ashore. She stranded on a sandy beach at Okaikokako (ironically a few metres from the Wahitapu burial ground where Barrett was interred nineteen years later) and was not seriously damaged. A party of Maoris assisted in hauling her off and she was safely anchored. During the unloading of stores a heavy cask of pork slipped from a sling in the hold and smashed through her bottom. She filled and became a total loss. (An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand refers to the ship by the name the Maoris gave her-Tohora-the Maori word for whale.) Barrett set up his whaling station and trading post at Ngamotu. Here he and his companions were welcomed by the Atiawa tribe, who no doubt realised that the Europeans, with their muskets and cannon, could be of assistance in their continuing wars with their northern neighbours. Barrett and Love were given two daughters of an Atiawa chief, Rawinia and Mere Ruru, whom they later married. The whalers joined the rigorous life of the Maoris, and indeed helped them in their terrible battles with the invading Waikatos. They saw men, women and children killed, cooked and eaten-some of them eaten before they were killed-and only their courage, intelligence and personal reputations saved them from similar fates. Inter-tribal raids had long been a feature of Maori life. Their history is largely a story of inter-tribal warfare and, at the time written history began, a little before Cook's arrival, the whole aspects of warfare was about to be changed with the introduction of firearms and new methods of fighting. In the early 1780s terrible battles occurred, with awesome casualties. Some districts were almost depopulated. I3 William Colenso, missionary, explorer, botanist, politician and New Zealand's first printer, made several expeditions from the East Coast into central North Island districts and in his Journals record' "From 1812 to 1827 was a truly fearful period in New Zealand. " blood flowed like water and there can be no doubt that the numbers killed during these fifteen years, including those who perished in consequence of the wars, far exceeded 60,000 persons.

The Atiawa's traditional enemies were the Waikato tribes, and details of their invasions southwards into Taranaki territory have been well- documented: the massacres ofPukerangiora, Tataraimaka and attacks on other pas and sacred places, and the fate of hundreds of the Atiawa tribe until they retreated tothe comparative security ofthe Otaka pa at Ngamotu.

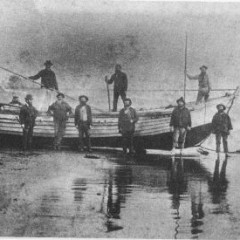

To set the scene for European settlement of what later became New Plymouth and because Europeans were involved, the battle for Otaka, culled from many and various accounts, is described here in some detail. In February, 1832, the Waikatos, sated on human flesh and blood following the massacre at Pukerangiora, yet thirsting for more, sent messengers ahead to enlighten the Atiawa of their coming. No doubt such a ploy was intended to strike fear into the hearts of their intended victims. But though the spies learnt of the presence of Europeans, they failed to appreciate the alien nature of European thinking and action. There were eleven 'foreigners' in the Otaka stronghold-s-John Love, Bosworth, Bundy, Oliver, Wright, Philips, Akers, Lee (thought to be a Negro), Keenan, Sheridan and Barrett. In addition to a determination to survive, the fortification possessed three cannons-one of which is now in the Taranaki Museum-which played a major role in the battle. The little pa (the site is now occupied by the Taranaki Producers freezing works) was readied for defence. The gardens were filled with crops ready for picking. Other food was harvested from the sea. There was no worry about water as good streams ran close by the palisades. Trenches were dug and a wooden tower built inside the palisade from where a chief could direct the course of the battle. The three cannons were sited to the best advantage. The first, named by the Maoris Rua-kura, guarded the eastern end of the pa facing the direction of what is now New Plymouth; the second, One-poto, stood in the centre, and the third, Pu-poipoi, occupied the western corner facing the offshore islands. Love and Barrett had neither grape nor balls for their cannon, so the time waiting for the battle was spent in collecting quantities of nails, scraps of iron, broken bottles and small stones for use as ammunition. The confrontation began quietly, with an invitation from the Waikatos for the chief of the Atiawa to meet on the beach and talk. This, against the advice of the Europeans was accepted.

The Atiawas were then urged to invite the Waikatos inside the pa to trade and become friends. This time Barrett's advice to refuse was heeded, albeit reluctantly, and the angry Waikatos flung themselves at the pa. The first day there were dozens of hand-to-hand encounters, but the defences held and at evening the invaders retreated and satisfied themselves with volleys of musket fire into the pa. Accuracy was not a feature of Maori musketry and the result was more noisy than dangerous. The Atiawa had about 100 firearms compared with the Waikato armament of nearly 3000, but disciplined and accurate sniping by the Europeans, backed by the skilful use of native weapons and the accurate field of fire from the three cannons, won the first day. During the three weeks which followed there were bizarre and horrible scenes which gave Barrett and his men an illuminating insight to the ways of the Maori. The Waikatos would launch attacks, and time and again were repulsed. Then parleys took place-at first much against the wishes of the Europeans who could not understand such behaviour in time of war. This would result in further attacks and more talk.

During the long intervals between fighting some incredible scenes took place. The Waikatos had come to Ngamotu without food, intending to live off the land; but the siege had developed into a situation which offered no such amenities and the only sources offood were the corpses which lay on the beach, and from the enemy. There was no difficulty in arranging for the latter. The Atiawa looked longingly at the thousands of Waikato muskets which the owners were perfectly willing to exchange for dried fish and potatoes. The Europeans were dumbfounded, but as their only hope of survival lay in the possession of more firearms, they added blankets and some tobacco to the currency, and so strengthened their armoury.