5

The towering shape of the oil-gas-fired power station dominates the

scene at Port Taranaki. The 220-metre-high chimney and its huge

slab-sided generating houses, monuments to power, dwarf the historic

rocks, Moturoa, Saddleback, Mikotahi and Paritutu, which guard the

harbour.

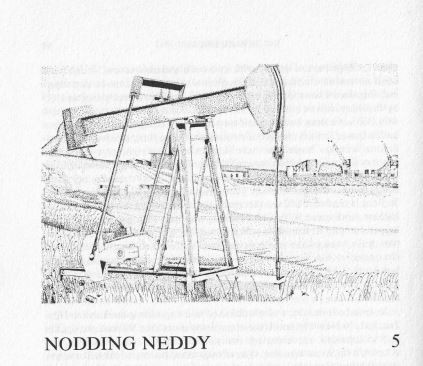

A kilometre to the east, among other memorials with which this

historic area abounds, there is another monument, smaller, but no less

significant. It is a clumsy steel gantry affair which for more than 40 years

nodded its life away, like one of those large-beaked and ever-thirsty

glass birds, a children's novelty of the 1940s, which spent its existence

taking sips from a coloured liquid in a glass in front of it. It is all that

remains of a beam pump; its working parts were dismantled in 1972. It

straddles the site of one of four oil wells which for many years steadily

produced high quality crude-oil from one of the oldest known oilfields in

the world. It bears the following inscription:

'This pumping unit stands as a memorial to those

who spent their time and risked so much in the

search for oil in Taranaki 1866-1972.'

It was in this area that the search for oil began in 1865, only six years

after Colonel Drake drilled the world's first oil well at Titusville in

Pennsylvania. Oil floating in the sea of Moturoa was observed centuries ago. The Maoris believed that Seal Rock, part of the chain of Sugar

Loaves, was once an island of bituminous matter set on fire by some

supernatural force and burnt to sea level. The first Europeans at

Ngamotu had only to disturb stones near the beach and small deposits of

thick oil were revealed. Often the sea near the beach was covered with a

thick, oily scum.

The 'father' of New Zealand's oil industry was E. M. Smith. His

nickname, 'Ironsand', was an indication of his involvement in another

promising Taranaki product-he was the founder of an iron foundry,

using the black sand which abounds on the beaches to produce iron and

steel.

Early in 1865 'Ironsand' Smith collected samples of oil from the beach

and sent them to the Birmingham Chemical Association. 'A splendid

report on the character of the oil' was received and Smith, encouraged

by fellow-pioneers, Carter, Scott and Ross decided to exploit the oil

deposits.

On December 22, 1865, the Carter Syndicate was granted by the

Taranaki Provincial Council a two-year lease of 26ha in the Sugar

Loaves area.? It was the first of more than 50 companies, most of them in

New Plymouth, formed specifically to exploit oil, between 1865 and

1950. Many failed to raise sufficient interest-or capital-to acquire the

necessary equipment; most of them drilled holes which were either dry

of yielded more sea water than oil; a very few were moderately

successful. In all 48 wells were driven in New Plymouth, most of them in

the Moturoa area.

'Ironsand' Smith and his companions started work-with pick and

shovel-and almost immediately met with success: On January 18, 1866,

the settlers received electrifying news. Oil had been found! More than

oil, in fact. At six metres the men encountered gas in such quantities that

they were driven from the workings. When one man collapsed and was

taken to hospital the other three set up a wind-sail to ventilate the shaft.

This could only be operated when the wind was blowing, and consequently

much time was lost. But by March 17 the well was down to 20

metres and small quantities of flowing oil were being taken. The

Taranaki HeraLd reported: 'This oil is thick and of greenish colour. It has

the genuine oil smell, but not as strong as the purified oil'.

Smith went to Nelson and bought an old waterdrilling outfit which he

shipped to New Plymouth with great difficulty and unloaded it near the

well, which had been named Alpha. A wooden sign was nailed to the

wooden derrick, 'To Oil or London', and cable-tool percussion drilling

began.

The news spread. From Melbourne came an application to the

Provincial Council for a nine-year lease over a wide area of the New

Plymouth coastline.

Public opinion was incensed by this proposed invasion by 'foreign' interests and the council decided-but only by a narrow margin-not to grant the application. During the debate onecouncillor who favoured the proposal foresaw 'locomotives beingdriven by oil and the waters of out future harbour ... ploughed by steamvessels whose motive powers are generated by its combustion'.

Drilling at Alpha continued. At one stage it achieved 80 gallons of

crude a day, but this was not maintained. In November, when the

primitive tool had reached 60 metres, the partners decided to cry quits

and sold their rights and equipment to the Taranaki Petroleum Company,

in which Carter also had a controlling interest. It had a concession

over 50ha, divided into three separate areas. Also founded the same

month was the People's Petroleum Company, with a lease over 2ha.

Chairman was Julius Vogel (later Sir Julius Vogel, Prime Minister). Its

well was christened' Victoria' on the Queen's birthday. No show of oil

came, and in 1867 the Taranaki Petroleum Company took over its assets.

This meant that much of the area in which oil in various quantities was

found during the subsequent century was under control of Carter. In

each of the three concession areas shafts were sunk, named 'Beta',

'Taranaki l ' and 'Taranaki 2' , and work was resumed at Alpha. It was

this well which appeared most promising, for on July 9, 1876,4 thick oil

was being produced at 90 gallons a day. But once more production did

not last; interest in this and the other three wells waned, and in 1888 they

were abandoned. Oil was still to been seen floating in the sea in calm

weather, but the fact that several thousands of dollars had been spent

without result during the previous 23 years was enough to quench

enthusiasm.

However, the world's need for oil was growing. The Moturoa

experience had made quite an impression on industrialists and geologists

in England and Australia, and there were still people convinced there

was oil to be obtained in New Zealand provided sufficient money and

experience was available. One of these was Henry Gordon, inspecting

engineer of the Mines Department. Late in 1888 he made an extensive

survey of the Taranaki area. He found that 'petroleum exists over a large

area, and it is only a question of boring to the requisite depth to get at its

source which was at a depth much greater than 700 metres.' Concluding

his lengthy report he said: 'I do not anticipate that petroleum in quantity

will be found at even a moderately shallow depth; therefore I think a

good boring plant is indispensable for prospecting ... it has also to be

borne in mind that in prospecting inland there are a good many chances

against striking petroleum in the first borehole, even if there is a large

supply in the locality.'

Gordon's report aroused much comment. The London Morning Post,

in a tirade against the apathetic attitude towards the needs of the British

Empire, said 'oil was being found in almost every important British

colony' and 'for the moment the most interesting are the oil deposits in

New Zealand'. (Oil exploration had by this time extended to the South Island and the east coast of the North Island). Finance was the stumbling

block. The. london Globe: 'It used not to be the way of Englishmen to

Ieave unutilised sources of wealth beyond the dreams of avarice. Let

dlamonds or. gold be found in any part of the Empire and British millions

flow thIther in a moment' .Charles Marvin, a noted oil expert of his

day: 'It is curious that while millions are invested by the public of this

country (Britain) in purely speculative gold mines, hardly any funds are

devoted to sinking wells for petroleum in Burmah, Canada and New

Zealand. In America, hundreds of times over, a single well has proved as

remunerative as a gold mine, such is the demand for it; English investors

have hitherto Ignored petroleum undertakings'.<br.

Vogel went to London. He was able to rouse sufficient interest on the

Stock Exchange to form, in July, 1899, the New Zealand Petroleum and

Iron Syndicate. This company had a nominal capital of $60,000. Its

state~ intention was to develop the petroleum deposits and to use the for

smelting the surrounding Taranaki ironsands. (This was the unrealised

dream of engineers and industrialists for more than 100 years. In 1865

Ironsand Smith first put forward the idea of exploiting the ironsands,

with only moderate success. Vogel's vision of using the district's oil for

this purpose remained a vision. It was not until 1970 that Bryan (later Sir

Bryan) Todd, a partner in the oil consortium, Shell BP and Todd, which

by that time had discovered gas and oil in the province, formed the

Viking Mining Company in association with American Marconi interests,

for export to Japan of more than one million tons of ironsand

annually from the Waverley district. The first shipment of 42 000 tonnes

left for Japan in July, 1971). '

But in 1889 the New Zealand Petroleum and Iron Syndicate informed

would-be~ subscribe:s a simple truth which has long been understood by

Oilmen: The quantity of supply can only be determined by drilling.' It

pointed out that up to that time 55,000 oil wells had been sunk in

America, only a fraction of which were successful.

Vogel and O.liver Samuel, a member of the House of Representatives

who was also m London and who had been appointed the syndicate's

chairman, bought a drilling outfit in England for $6000 and shipped it to

New Zealand. Before it arrived, the venture suffered the first of its many

setbacks.

The death of Charles Marvin who had been appointed

managing director. F. P. Corkhill took his place and a Canadian oilman

named Booth was employed as head driller. Operations on the Booth

well, named in his honour, began in May, 1890. In July Booth reported:

We are down to 900ft now and are in oil. The most valuable oil I have

seen. The Success of the company is now certain.' Recommending

further wells should be sunk, he added: 'The company must get a man

who understands refining, as I do not profess to do this.' The London

directors were not impressed. After frequent requests for money to pay

the workers and Import new machinery,