5:3

It was at this stage, says Freeman, that the secretary ofthe company

told the shareholders that the Standard Oil Company cabled a big

advance on their last offer. MacPherson, whose personal attendance in

America was imperative to complete the negotiations,' had only just

time to rush down to the harbour and catch the American boat when the cable arrived. 'The trip to San Francisco from New Zealand took about

four weeks. But long before the Mariposa arrived there, after calling at

Samoa and Honolulu on the way, people began to talk. Some ugly

rumour got about. There had been no further cables from Colonel

Anderson or from the Standard Oil Trust. It took us some time to find out

that MacPherson had never reached San Francisco ... on investigation

it was found that the whole of the funds had been changed into American

currency and that MacPherson had got away with the lot. He had

probably left the boat quietly at Samoa and booked a passage to America

of Europe on another boat and under another name ....

'I have set down, to the best of my recollection, the principal details of

the most amazing and artistic swindle 1 have ever seen. At the cost of an

initial outlay of a few hundred pounds, and a temporary bank draft of

twenty thousand from their American accomplices, MacPherson and

Anderson had got clean away with the best part of one hundred thousand

pounds.' Freeman surmises it cost about 'a thousand or two' to bribe the

man with the wagon who had also salted the soil. But the secret of

MacPherson's 'extraordinary influence' never leaked out. 'Some of it,

no doubt, was due to MacPherson's cultured and magnetic personality

which temporarily deceived even such experienced men as the Premier

and Mr Ward; although at the last moment they must have suspected

something, when they held aloof ... quite a lot of people did not want to

talk about this amazing swindle afterwards. For important businessmen

never like to admit that they have been fooled ... .'

Freeman was 81 when he wrote all this almost 40 years after the event.

The fact that he was able to set down word-for-word conversations and

transactions after all this time could well be regarded with some

suspicion, as could the apparent absence of any official investigation

into such a large-scale swindle. There is little doubt, however, that

during this period, and later, there were irregularities by company

promoters and sharepushers which bought oil exploration affairs in New

Zealand into disrepute.

After the Samuel syndicate wound up its affairs in 1901 there was little

activity in the Taranaki oilfield for several years. The fire had gone, but

the spark was still there. It was fanned into brief flame in 1904 by G. E.

Fair, who had been a member of the syndicate. With small backing from

a group of Adelaide businessmen he founded the New Zealand Oilwells

Company which bought the rights of the Samuel syndicate, but after

spending about $5000 in equipment and drilling to 700 metres in a hole

near the Hongi-Hongi Stream without success, its affairs were taken

over by the Moturoa Petroleum Company, with J. B. Roy and Fair at the

head. Drilling continued on the existing hole, renamed the Birthday well

on Roy's birthday, and when the bit had reached about 800 metres it

blew out' immense quantities of oil'. This led to great excitement in financial circles and within a few days shares which were quoted at $56

were selling at $120 in Auckland and $117 in Melbourne.

The Christchurch Truth reported: 'It really looks as if Taranaki has

struck oil at last. It has got a well which is turning off oil at a barrel a

minute and Taranaki, in a very excited condition, is sitting on the nozzle

to keep it from breaking loose altogether ... shares that were not worth

setting fire to have gone up like an unballasted balloon in a high wind,

and a delirious province is setting up drinks for its friends. Taranaki will

now proceed to give John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Concern

an awful time. Taranaki deserves its luck and if only its ironsand gets

floated its cup of joy will overflow worse than its solitary well. ... ' The

Governor of New Zealand, Lord Plunket, visited New Plymouth and

described the well as one of the most important features of the industry's

future.

It was against this background that the Moturoa Petroleum Company

Ltd announced that it has fulfilled the purpose for which it was formed,

'The discovery of payable oil free from water,' and that it was now time

for a new concern to be established with the object of exploiting the

'wealth that lies under Moturoa'.

The second Taranaki Petroleum Company was formed at a meeting in

Wellington late in June, 1906, at which G. E. Fair was appointed

managing director. The directors decided that more holes should be

sunk; and efforts were to be made to find a suitable market for the oil.

The best available offer up to this time was a little over Ie a gallon of

crude, from the New Zealand Government, offered more as an

encouragement than on account of the Government's need for crude. It

was decided the only way to sell the product was to refine it, and to this

end one of the first acts of the board was to obtain quotations for a

refining plant.

Several barrels of oil were sent to A. F. Craig and Co., of Paisley,

Scotland, for analysis. 'This oil ... is the most superior we have

examined,' came the reply. 'The refined products are of exceptional

quality, colour and smell and there is a large proportion of wax of high

melting point ... the crude petroleum contains only a very small

proportion of unsaturated hydrocarbons and resembles in character and

purity Pennsylvanian petroleum.' This analysis was very similar to the

one made by the New Zealand Government analyst.

Armed with this report the Taranaki Petroleum Company approached

the Government for a loan of$20,000 specifically to build a refinery. The

request was shelved 'for consideration'.

Meanwhile the Birthday well was kept sealed, new holes were drilled

nearby, and existing ones reopened, resulting in the production of

enough crude to cause embarrassment. Large underground tanks were

filled; there was little or no local market, no refinery, no means of

exporting it where markets might have been found.

It was then that an experiment was made with a locomotive

equipped to burn Taranaki crude oil in a trial run from New Plymouth

to Wellington. A reporter who travelled with the train wrote: 'The

trial seemed to be quite satisfactory apart from the smoke and the

smell trailing over the landscape. It was noteworthy and comical to

see how other railwaymen took the passage of the consumer of

Taranaki oil. Some raised their hats ironically to us and with the other

hand held their noses.' New Zealand Railways kept its counsel on the

results of the trial.

During the period of the takeover of the Moturoa Petroleum Company

in 1905 the seeds ofadispute which came to a head in 1907 and 1908 were

sown. This involved allegations of 'salting' the wells with previously

recovered oil, with the object of influencing the share market at a critical

time. Some very heated meetings of shareholders were held, at which it

was charged that at least two directors had sold their shares while the

price was at its highest. The allegations were denied as fiercely as they

were made, and votes of no confidence were defeated after lengthy and

loud debates. The 1908 annual meeting was informed that employees

had been threatened with instant dismissal if they mentioned petroleum

matters outside the works. It was discovered that the Birthday well,

renamed Taranaki No.1, upon which hopes of the new company were

founded and which had been capped when it was found to contain

'immense quantities of oil', was a non-producer, and it was this fact

which raised shareholders' suspicions and ire.

To stimulate both drilling and production the Government on June 1,

1909, offered a bonus of' £2500 to the first company which produced

250,000 gallons of oil, and another £2500 for the first 500,000 gallons of

refined oil' .The Taranaki Petroleum Company won both bonusesthe

first immediately; the second four years later when the country's first

refinery came on stream.

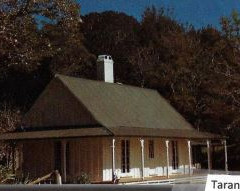

The erection of 420 tons of equipment valued at $45,000 gave

employment to between 80 and 100 men. A special measure was passed

by the Government, enabling the land to be sold to the company. It

occupied an area of about 4ha, and an avenue of trees was planted on the

driveway, which can still be seen on the south side of Breakwater Road

opposite the cool store, now leading nowhere.

Total cost of the refinery was $79,000 and it was completed in 18

months. On June 17, 1913, at a gala ceremony attended by the board of

directors, local body leaders and leading New Zealand businessmen, oil

was directed into the refinery for the first time. J. D. Henry, technical

adviser, explained that it would be at least three weeks before oil was

fully refined. 'We must go through all the refining stages from A to Z

because, for one reason, our most valuable product is the last one

(paraffin wax). All other products must be drawn off before we get to the

wax, and as it is wax which gives our crude unequalled commercial value

amongst the oils of the world, it would be financially unsound-indeed, I

may say mad-to sell it as oil or in a residual or fuel oil state.'The fires were lit under the three stills on June 1, and the oil was turned

into the stills 16 days later by Captain Halsey, of HMS New Zealand.

When the refinery opened there was stored in underground tanks nearby

more than half a million barrels of crude oil, which was being added to all

the time. By 1913 the company's No.3 well earned a 'record for the

world' in that it had been running continuously for three years without a

pump; and No.5 was continuously erupting while the refinery was being

built.

One of the first users of the New Plymouth refined benzine was Mr

Okey, the Member of Parliament for New Plymouth, who with Mr

Wilkinson, the Member for Egmont, made the trip from New Plymouth

to Wellington in a motor car using the new fuel. 'The journey was

covered without the slightest mishap,' reported the Dominion.

Oil rigs were 'sprouting like mushrooms' in many parts of Taranaki

during this period. Thirteen other companies had been formed between

the time of the refinery'S purchase and the time it came into production.

Lord Ranfurly, chairman of Taranaki (NZ) Oil Wells Ltd formed in

London to finance the refinery, said that 'as this was the only refinery in

the Southern Hemisphere, all oil from these wells would be bought and

distilled by the Taranaki Company'. Calculations showed that even 'by

paying so much as fourpence a gallon' the company would make an

annual profit of $48,000, sufficient to pay 5% dividend on the capital. I 6

For a time this sort of claim seemed justified. During the latter part of

1913 production kept the refinery working almost to capacity. The half

million gallons in the storage tanks was soon refined, as the continuing

production from the wells. But the refinery was costing a lot of money to

run, and it was soon evident that more capital would be needed if the

venture was to succeed.

One of the many reasons for the failure of so many oil-seeking

ventures, including the refinery, was financial. In about 1913 the cost of

sinking a well to 400 metres was about $1000. It was not therefore, the

actual drilling operations which ruined the companies, but the colossal

vendor and promotion profits, management fees, and the sometimes

mysterious losses of capital. For instance, Taranaki Oil Wells Ltd had

been formed in London by H. J. Brown, chairman of the British Empire

Trust, with a capital of $800,000-enough to sink 800 wells. Its purpose

was to develop the Moturoa oilfield and to erect the refinery. Chairman

was Lord Ranfurly and other directors in London included Sir George

Clifford. (New Zealand representative), the New Zealand board comprised

C. Carter (chairman); H. Okey, MP, J. R. Roy, J. J. Elwin and C.

E. Bellringer.