1:2

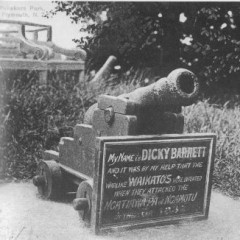

In the third week of the battle the schooner Currency Lass arrived off the beach at Ngamotu and was immediately surrounded by canoe loads of hostile Waikatos. The skipper quickly stood off shore. Somehow Love managed to swim out to her to warn the captain of the situation ashore and advised him to leave rather than risk the ship falling into Waikato hands. Covering fire from the pa and from the ship kept the Waikatos at bay, enabling Love to make the return swim. For the first time the Waikatos appealed directly to the Europeans, and Love agreed to talk to one of the chiefs. The meeting took place aboard the Currency Lass and Love, convinced that treachery would occur, refused the Waikatos' offer that in exchange for the surrender of the pa, Love and his companions would be guaranteed their lives. Meanwhile a small party of Ngati Tama reinforcements from Tonga- porutu managed to reach the pa from the north and this gave the defenders new heart. The battle resumed next day with increased savagery. The cannon fire was withheld until masses of Waikatos were assembled close to the palisades, and the result of their salvos was terrible. Hand-to-hand encounters continued all day, and at evening the Waikatos had had enough and retreated some distance to the north. The first battle was over. The Atiawas began collecting their spoils. The dead were fortunate; for them it was the cooking fire. But the wounded and the captured were subjected to the same horrible tortures the Waikatos had used against victims oftheir raids on other Taranaki pas. In the midst of this savagery the bodies of thirteen Atiawa sub-chiefs were buried with barbaric honours. It was customary to bury valuable articles with honoured men. There was little left of value save weaponry. Barrett and his men watched with amazement as, in spite of the fact that the Atiawas knew that their fight with the Waikatos was probably not over, eight muskets and a quantity of ammunition were placed in each grave-a total of 104 muskets. During the following days the Waikatos withdrew farther north, and the Taranaki Maoris left the area; only about 300 refused to leave their ancestral home. The white men also left to migrate to Nelson and Marlborough, where Barrett established another whaling station and later a trading post at Port Nicholson. The 300 Atiawa fortified the rock Mikotahi, and for a year they lived a frugal life, still fearing the return of the Waikatos. This indeed occurred in 1833. A siege lasted for almost a year until the defenders surrendered their fortress in exchange for the lives of those who remained. The Waikatos then massed their forces and headed south, conquering pa after pa until they came up against formidable opposition at Orangi- tuapeke, where they suffered great losses. A feast was arranged and the respective chiefs, Te Wherowhero of the Waikatos and the Matataka of the Taranaki tribes, arranged a truce. Te Wherowhero solemnly promised to return to his home, taking with him his captured slaves. The Waikatos never returned in force. This was the situation at Ngamotu when Barrett returned five years later with Colonel William Wakefield, chief agent of the New Zealand Company, to be welcomed by a handful of Atiawa, still living in fear on Mikotahi. The Wakefield system of emigration was born from the need of Britain to solve the problem of over-population. In the early Victorian age 'Edward Gibson Wakefield emerged as the advocate of "systematic colonisation" (the planting of a cross-section of British society in well-organised new colonies) and his theories were given imperfect expression in the South Australian Company and the New Zealand Company. '15 It was claimed the removal of people from over-populated Europe to under-peopled areas of the globe was 'a work of eminent social usefulness'. The New Zealand Colonisation Company was formed in 1837, following the collapse of another 1826 undertaking after buying land at Hokianga and which the New Zealand company took over. Wakefield's scheme, which had the backing of many men of influence and talent, provided for the purchase by future emigrants in Britain, of large areas of land in New Zealand, the purchases to be confirmed later. It met with opposition from Marsden and other missionaries who had established themselves in various parts of the country since 1814 and had for long abhorred the 'evil influence' of Europeans upon the Maoris. The British Government, suspicious of all colonial developments following the then recent failure in America, felt 'no legal or moral right to establish a colony without the consent of the Maoris' .16 The New Zealand Company appointed agents in various towns in England, and one of them, Thomas Woolcombe, proved most energetic. Largely through his efforts it was decided to form a subsidiary company at Plymouth in the west of England. Called the Plymouth Company, its function was to stimulate emigration among farmers and labourers; to sell land (not yet bought) to selected emigrants destined for New Plymouth (not yet named). By December, 1840, it had sold land to the value of $25,000, but in spite of this the company, never a strong one, surrendered its main activities to the parent body, retaining its directors as a committee to continue selling land and selecting emigrants. This arrangement was maintained until the end of 1842 when the Plymouth Company was abolished. The company's memorial lies in the form of streets named after its directors, who included the Earl of Devon, Thomas Gill, Sir Anthony Buller, Captain Budleigh, Lord Eliot, Richard Willis, John Hine, George Leach, Sir Charles Lemon, E. W. W. Pendarvis, Edward St Aubyn, Hussey Vivian, Lord Courtenay, John Buller and Woolcombe. Meanwhile the New Zealand Company's project had taken shape. Wakefield had organised a preliminary expedition in the Tory which sailed from Plymouth on May 17, 1839, arriving at Blind Bay (now Tasman Bay) on August 17. Aboard were Colonel William Hayward Wakefield, the principal agent for the New Zealand Company, and Edward Gibbon Wakefield's son, Edward Jerningham. Fourteen days later the little sailing ship arrived at Te Awaiti in the Tory Channel, where it was met by Barrett. 'His wife Rangi (Rawinia), a fine stately woman, gave us a dignified welcome ... he had three girls of his own and had adopted a son of an old trader and friend of his, named Jacky Love, who was on his death bed regretted by the natives as one of themselves.' 17 After exploring the Marlborough Sounds and the Port Nicholson area, Wakefield sailed north, with Dr Ernst Dieffenbach, a German scientist and explorer, and Barrett, both of whom were left at Ngamotu in November 1839 to prepare the natives for the sale of land while the Tory left for the north. They were welcomed by the remnant of the Atiawa, to whom Barrett spent the next two months as an interpreter to the Wakefields, explaining the reason for their presence. It is doubtful if the Maoris fully understood the implications of the mission, for Barrett, although having lived with them for many years, had never mastered the language, and communicated with them in a mixture of poor English and poorer Maori. On February 15, 1840, the New Zealand Company's impressive Deeds of Sale were translated by Barrett at Ngamotu, when the complicated provisions were explained. Seventy-two' signatures' were appended, including that of John Dorset, acting agent for the company. The land acquired extended from a spot halfway between the mouth of the Mokau River and the Sugar Loaves, to south of Cape Egmont, inland to the summit of Mount Egmont, and from there to a high spot on the Wanganui River. 'Many of the true owners were absent, while others had not returned from slavery to the Waikatos in the north. Thus the seventy-two chiefs of Ngamotu cheerfully sold lands in which they themselves had no interest, as well as lands wherein they held only a part interest along with several others.

It was the myth that France was contemplating the annexation of the country which probably prompted the Government to refuse to sanction Wakefield's actions. Instead they sent out a man-of-war under command of Captain Hobson to treat with the Maoris for the recognition of British sovereignty. Three days after the Taranaki chiefs had signed the agreement with the New Zealand Company, Hobson concluded the Treaty of Waitangi, under which the Maoris ceded to Great Britain all rights and powers of sovereignty in return for confirmation 'in the full and exclusive possession of their lands and estates'. Following this the company received official recognition by London. Thus two powers were established: the Governor in Auckland which Hobson had chosen as the capital, and the company at Wellington. They championed different interests and opposing policies; the company wanted land, as much and as soon as possible; the Colonial Office-and the treaty-said the land belonged to the Maoris. The two authorities struggled and bickered. A company official wrote to the Colonial Secretary in London: 'We have had very serious doubts whether the Treaty of Waitangi, made with naked savages by a consul invested with no plenipotentiary powers, without ratification by the Crown, could be treated by lawyers as anything but a praiseworthy effort for amusing and pacifying savages for the moment.' The 'naked savages' realised the treaty with Hobson clearly distinguished between the shadow of sovereignty, which they had surrendered, and the substance of property ,which they had no intention of losing. If they lost their land their tribal life would be extinguished. The complex tribal laws exasperated the settlers who genuinely thought they were dealing with the owners, and the dispute grew. William Spain was appointed by Lord Russell, Colonial Minister in London, as a commission to inquire into the 20 million acres claimed by the New Zealand Company in various parts of the country. In May, 1842, he heard the claims of the Wellington district (the company's first settlement). It was soon apparent that Wakefield's hasty purchases there were faulty and that the settlement of the claims would be a lengthy business. Meanwhile, the development of the town of New Plymouth was proceeding, albeit with difficulties. Carrington's first task was to decide on a site. He andhis party of assistant surveyors arrived at Ngamotu on February 12, 1841, on the barque Brougham. A few weeks later he wrote to Thomas Woolcombe, managing director of the Plymouth Company, 'I have much pleasure in informing you that I have selected a place where small harbours can be easily made and with trifling expense, close to an abundance of material being on the spot I have fixed the town between the rivers Huatoki and Henui two or three brooks run through the town and water is to be had in any part of it. The soil, I think, cannot be better. There is much open or fern country and an abundance of fine timber. We have also five rivers between this and the Waitara, a distance of about twelve miles. I have twice been up this river, once at low water for three miles. The banks are parallel and the country and river beautiful. I once had made up my mind to have the town there, but the almost constant surf upon the bar has caused me to prefer this place ... the Plymouth Company has the garden of this country; all we want is labour and particularly working oxen.' 19 Some of the labour arrived in the William Bryan (312 tons) on March 30, 1841. It also carried George Cutfield, in charge of the expedition, Richard Chilman, his clerk Thomas King, A. Aubrey, and Henry Weekes, the surgeon. In addition there were in the steerage 42 married and 22 single adults and 70 children: that was the labour, but there were no oxen. Describing the troubles the new settlers had, Cutfield wrote to his directors: 'I erected tents and procured different places of shelter for the people from Mr Barrett-rough certainly but better than being out of doors ... I have in consequence to remove the stores and baggage along the land and over the Huatoki which is about fifty feet across to the, storehouse of the town. In order to do this I have had to construct a bridge over the river. You will be fully aware of the great difficulty we have had in the transit of these goods with the small means at our disposal which consists of but one timber dray, two handcarts and six wheelbarrows, the narrow wheels of all cutting deeply into the sand. The traction had to be entirely manual. A pair of bullocks or a horse would be of invaluable service to us and a great saving of expense to the company.' Oxen and horses arrived on later ships, but the building of the storehouse and the bridge must have entailed great effort. The former took the carpenters three weeks to construct and the bridge was 'built by labourers who had to carryall the timber used in its construction and some of it a distance of two miles', wrote Cutfield. 'It is strong enough for a horse and a well-loaded cart.' Cutfield's impression of his new home land: 'This is a fine country with a large quantity of flat land, but every part is covered with vegetation, fern, scrub and forest ... there are thousands of acres of this land which will require but a trifle of outlay to bring it into cultivation ... 'Rats are numerous and we require arsenic and a good breed of terriers, for I fear our stores and produce will suffer. Few natives have : been living here since the war with the Waikato tribe about seven years since. Consequently pigs and potatoes are scarce and as the native population is likely to increase I fear provisions will be still more scarce before the spring ... strong, warm clothing and large blankets will for a time be the best articles to barter with the natives. There is at this time no demand for guns or powder; blankets, blankets is all the cry. Nails and tools they always appreciate and they will I trust soon take to agricultural implements. They are quick in understanding, but very dirty and idle. Finer men I never saw, but the women are by no means prepossessing. Since we have been here there has been much talk of the Waikato tribe coming. Should they come with bad feeling I shall be prepared for them. However, I hope they know better than to molest the whites.' When Carrington began his surveying operations he employed most of the Europeans working in the community as well as some Maoris with whom he had mild disputes-not because the Maoris disputed the sale of the land, but because they said they had not received all the goods they had been promised in payment. By the time the second ship, the Amelia Thompson, carrying Captain Henry King, Chief Commissioner for the Plymouth Company, 'his lady and son, and 187 passengers', arrived on September 3, buildings had been erected, gardens planted, and wheat sown; streets were named and their lines were delineated according to Carrington's plan. Other ships to arrive in the first two years of settlement were the Oriental (506 tons with 130 passengers) which arrived on November 1, 1841; the Timandra (130 passengers) February 24, 1842; the Blenheim (374 tons) November 7, and the Essex (392 tons, 115 passengers) January 25, 1843. These six ships plus the Brougham were the vessels which transported the 'original pioneers' of the colony of New Plymouth. Barrett and his men were always there to assist them ashore and to help them set up their new living quarters. In addition the Regina, a baggage and store ship, sailed from Plymouth at the same time as the Amelia Thompson. She was a schooner of 164 tons, a new staunch oak-built vessel owned by Edwin Henry Rowe of Devonport. She cost $2600 and was under the command of Captain Nicholas Browers. She arrived in New Plymouth on October 3, 1841, and while unloading was blown ashore 'on a reef near the northern end of Queen Street'. 20 Her crew of eight landed safely and all her cargo was saved, but she was declared a total wreck and on November 18 all that was left of her was sold at auction of John Leuthwaite for $150. This was the first of many vessels of all sizes which fell victim to the surf until the New Plymouth breakwater was built 40 years later. The emigrants to New Plymouth were classed as 'good yeoman stock"." This was in contrast to the position regarding Australia which contemporary historians had described as 'colonisation by paupers and convicts' until complaints by colonists stemmed the tide of adven- turesses following the dispatch of a shipload of prostitutes to Sydney. The following advertisement appeared in London and Plymouth papers in 1841