1:3

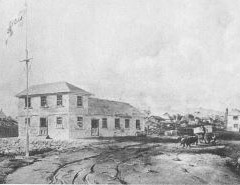

'New Plymouth, New Zealand. The Court of Directors of the New Plymouth Company do hereby give notice that the new ship Timandra AI, 430 ton burden, is chartered for the conveyance of cabin passengers and free emigrants to the settlement of New Plymouth to sail from London on the l Oth and from Plymouth on the 20th October. The settlement to which about 500 persons have already emigrated from the West of England has been located in the district of Taranaki near the Sugar Loaflslands. Further sales ofland in England are now restricted to actual settlers who will receive liberal passenger allowance and the Timandra has been specially chartered on terms which will secure to families and others a passage to the settlement on liberal terms.' Charles Hursthouse in his Account of the Settlement of New Plymouth written in 1848 records that the cost of passages in most of the ship's chief cabins was '45 guineas for each person 14 years and upwards; 25 guineas for forecabin passengers and 18 guineas for steerage passengers. The figures for persons between seven and fourteen years were 27, 15 and 10 guineas. For those between one year and under 7 18, 10 and 8 guineas and there was no charge for babies under a year old.' Carrington came in for a deal of criticism regarding his chosen site for New Plymouth, mainly because it had no harbour. Meetings were held at which some pretty straight-forward talk was exchanged and at which 'the ever-present danger of starvation' was referred-> to, but the majority of the settlers supported Carrington. Although the want of a harbour was to be a sore point with them for the next forty years, his choice of the town's site was confirmed and development proceeded slowly. Carrington had land disputes to contend with which were not confined to the Maoris. These also involved him in wrangles with Barrett. At the time of the original purchase by Colonel Wakefield it was stipulated that the same amount of land should be reserved for Barrett and Love as for the native chiefs. There were some fairly heated words between them and Barrett said: 'Possession is nine points in the law. I have never been rewarded for my services. The company would never have had a bit of land had it not been for me, and unless they now reward me I am not going to give this up. '23 What, then, was to prevent Barrett from taking up land in the middle of the town after it was laid out, asked Carrington. Barrett's reply: 'Now I tell you, in like, when your town is laid out, I can go and take 500 acres right in the middle of it.' Carrington had other problems. He was short of men, short of equipment, short of transport, short offood, short of money-and short of friends in high places. Colonel Wakefield and the New Zealand Company's agent seemed opposed to everything Carrington did and succeeded in forcing him against his will to leave New Plymouth and New Zealand in September, 1843, under a cloud. But his town plan proceeded, and by 1847 Hursthouse records there were 1137 Europeans (612 males and 525 females); there were 210J% acres of land in cultivation, mostly wheat, oat and potatoes; there were 726 cattle, 48 horses, 898 sheep, 177 goats and 'numerous' pigs with imports of cattle and horses coming in increasing numbers from Sydney. In the meantime Barrett had maintained his position as one of the leaders of the little community. On March 28,1841, he was married to the woman with whom he had lived in what would today be called a de facto relationship. In the certificate of marriage, which was signed in the Wesleyan Mission House at 'Ngamoto, Taranaki' and was sent to the Registrar-General's Office in Wellington, the name of the bride was given as 'Wakaiwa, of Ngamotu', Barrett was described as 'a whaling master of full age' , his conjugal status (bachelor, widowed or divorced) was 'not registered'. In 1842 he made his last will, leaving 'one third of the rents, profits and income' from his business interests in Wellington and Taranaki 'to my wife, Wakaiwa, a Maori woman' .24 (The inscription on the Barrett Memorial at Wahitapu Cemetery gives the name as Wakaiwa Lavinia Barrett, Lavinia being translated to Rawinia-the name later given, as her memorial, to the Taranaki Harbour Board's pilot vessel.) Barrett was Colonel Wakefield's chief witness (and also the official translator) at Commissioner Spain's long awaited inquiry into the sale of land to the settlers in Taranaki. It had taken two years, and had involved the commissioner and Wakefield in much travelling, since the Wel- lington claims had been heard in 1842. 'The journey [to New Plymouth] from Wanganui occupied us ten days in consequence of bad weather and t he swollen state of the streams', wrote Colonel Wakefield. Spain's court opened in New Plymouth on May 31, 1844. George larke, Sub-Protector of Aborigines, put evidence on behalf of the Maoris. The hearing lasted for more than a week, and on June 12 Spain announced his findings. The company had claimed a block of 28,000ha: pain awarded them 24,000ha of 'legitimately purchased' land. 'The New Zealand Company upon payment of a sum of flOO ($200) in lieu of some double-barrelled guns which had been promised but not delivered (this money to be used for the benefit of the Maoris in the area) was entitled to a Crown grant of a block of 60,000 acres extending along the coast from the Sugar Loaves to the Taniwha Stream. However, excluding this block were all the pas, burying places and land in actual cultivation (48ha); native reserves equal to one-tenth of the block, i.e. 6,000 acres (2,400ha); 100 acres (40ha), for the Wesleyan Mission Station; 180 acres (72ha) for Richard Barrett and his family; and any other land which prior title to that of the New Zealand Company could be subsequently proved. '25 This award was satisfactory to many settlers, but was received with great hostility by the Maoris. Relations between the two races, which had geatly deteriorated since the Atiawa had- welcomed Wakefield, arew worse. Trespassing and petty robberies on lands of the settlers were intended to extort further payment for the land, or drive them from it. In response to appeals from both the settlers and the Maoris, Governor FitzRoy visited the settlement twice (in August and November). The result: FitzRoy formally set aside Spain's award, substituting it for 'a block of 3500 acres (l400ha) (the Fitzroy block) which included the town site and the immediate surrounding area', for which the company would pay $700. The deed was signed on November 28, 1844. (The original letter from FitzRoy to the company's agent in New Plymouth,.John Wicksteed, setting out his ruling in detail, is in the Taranaki Museum). FitzRoy's action meant that many settlers who had taken up land outside the Fitzroy block were compelled to move to within its precincts, with very meagre compensation for their losses. The Maori hostility towards the settlers increased (in Taranaki and elsewhere) an attitude which alarmed the Colonial Office and resulted in Fitzroys recall.

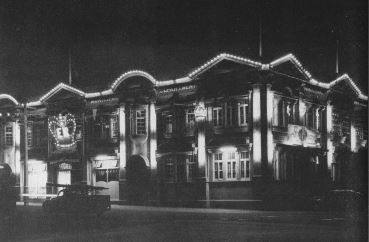

He was replaced by Govenor George Grey who tried to minimise the harm FitzRoys decision had done by repurchasing from the Maoris part of the company's original holding. This made little impression, however, and the Atiawa erected a boundary mark* on the banks of the Waiwakaiho River to indicate the limit of Pakeha settlement. It came to be known as the FitzRoy Pole. On it were carved two figures symbolising the triumph of the Maoris over the Pakehas. Historians disagree on many points about the FitzRoy Pole. Some interpretations of the carvings have the Pakeha on top, others that the Maori was dancing on the head of the Pakeha. One area of complete agreement is that both figures were naked except that the Pakeha wore a top hat. The Maori, however, possessed an appurtenance which is said to have been an affront to the Europeans and which kept most settlers with their Victorian morality away from the scene. An unnamed settler is said to have had the last laugh. He made a diversion to the pole with an axe and performed the unkindest cut of all-a severe circumcision operation. Sir Peter Buck= referring to possible Maori phallic worship, says: 'The frequent occurrence of the sex organs in Maori carvings is the natural accompaniment of the human body which is the common motif in Maori art. It is curious, however, that they are treated with suspicion by the general public which accepts as natural the similar treatment of marble statues. If in some carvings the carver has made the phallus unusually large the suspicion becomes a conviction unless it is realised that the artist was influenced by a bizarre sense of humour. Maori art is profane, not religious.' Known as Te Pou Tutaki, the pole was carved from a 7 metre shaft of puriri from the local bush. Beyond the pole, said the Atiawa, no land shall be sold to or occupied by the Pakehas. The pole was burnt by a gorse fire about 1885. The fate of its remains are uncertain; one report says it was chopped up for firewood by the Smart Roadjunction toll-gate keeper; another that parts of it were used as the toll-gate posts. A drawing by William Strutt, who lived for a time in New Plymouth, shows the Maori near the base of the pole, and a careful study of it (the original is in the Turnbull Library) leaves no doubt as to the figure's virility.* Barrett's death in 1847 was a severe blow to the young settlement, but it served, briefly, to enable the two races to forget their differences, as they remembered his services to both sides. Wicksteed recorded: 'There came a day when Barrett was killing a whale that had run unusually close inshore. Three boats from Richard Brown's station which had joined in the chase hung about within a short distance. Barrett had four boats and headed the seven-oared himself. ... The whale was spouting blood in a vortex of spume when Dicky Barrett ran in to put the finishing lance into its life. Suddenly the cry went up: "There she fluked. By joves, she's done for Barrett." The great tail appeared to fall on the boat which for a moment was lost to view ... but in fact the fluke had not touched the boat. All the mischief had been effected by the concussion of air as that terrible tail fell. But Barrett was unconscious. He was brought ashore and half-carried, half-walked by two strong supporters to Richard Brown's house, which was the nearest house. They were rivals in the whaling business but all knew that Mr Brown would do all in his power for his friend.' But it wasn't enough. Barrett never fully recovered. 'He aged rapidly' , wrote Wicksteed, 'and later died at his home.' Barrett was survived by his wife, and two daughters who married two Honeyfield brothers-Sarah to William Henry and Caroline to John. Memorials to Barrett include Barrett's Reef (between Moturoa and Saddleback Islands); Barrett's Reef in Wellington Harbour; Barrett's Lagoon and Barrett Road in New Plymouth; Barrett's Hotel in Wellington (a large house brought from England by Dr C. S. Evans) and which became 'the social and political hub of the new settlement in Wellington.>' It saw levees, banquets, stage shows and balls, and housed vice-royalty and politicians for many years. (Wahitapu Cemet- ery, where Barrett was buried, was part of land bought from the Maoris in 1842 by the Wesleyan Mission. In 1855 a strip of mission land was acquired by the New Zealand Railways, which included part of the cemetery, and in 1927, at the instigation ofW. J. Honeyfield, the Maori Land Court set aside an area of land officially to be called the Wahitapu Urupa. It was completely surrounded by Railways land, and after long negotiations between the trustees, the Historic Places Trust, Lands and Survey and NZR, a strip of land for access was obtained. In 1977 plans were put in hand to restore the derelict area.) Barrett's funeral was attended by leaders of both races. Any leavening of feeling between them was soon dissipated when Governor Grey acted on a letter from Gladstone, the British Secretary of State, dated July 2, 1846, which instructed him to inquire into the Taranaki land dispute. Gladstone hoped Grey would be able to 'give effect to the award of Mr Spain in the case of the company's claims at New Plymouth, and in any case I rely on your endeavours to gain that end so far as you have found it practicable, unless, indeed, which I can hardly think probable, you may have seen reason to believe that the reversal of the commissioner's judgement was a wise and just measure' _27 Grey quickly realised it would be impracticable to give effect to Spain's award, but he arranged a compromise solution whereby the Maoris received what he thought would be sufficient land for both their present and future needs, with the balance being made available for sale to settlers. Grey left Donald McLean, Land Commissioner for Taranaki, to carry out his instructions. By 1850, following protracted and difficult negotiations, more than 5665 ha of rural and urban land had been bought in a wide area around the town. This included several areas of reserves. In the Ornata block of 4856ha (bought on August 30, 1847, for $800 plus a cask of tobacco valued at about $50) 50 ha was reserved for Barrett and his family as compensation for land claimed by them under Spain's award, as well as several sites for public and native reserves. With sufficient land for its immediate needs, the settlement was again able to make some small progress. The New Zealand Company, having been rejuvenated by a Government loan, granted compensation in land to those settlers deprived of their holdings by FitzRoy in 1844. On July 4, 1850, the company surrendered its charter and all its holdings reverted to the Crown. The total population recorded in the December, 1849, census was 118928 an increase of only 98 persons since the first census in 1843. This indicated the troubled state of the area during the land problems. Worse was to come. In 1854 a feud among the Puketapu Maoris erupted over land sales policies. Widespread fighting ensued for some years. The settlers becamed increasingly alarmed and demanded protection, and British troops were stationed on Marsland Hill. When the feud ended in 1858 more sales took place and gradually all the land taken by FitzRoy 15 years earlier was acquired. The coveted Waitara area was still in the hands of the Maoris, and disputes over its sale were soon to lead to a disastrous and costly war.