6:3

This spurred the New Plymouth Council to join nationwide pressure for State roading finance. The result was the establishment of the Main Highways Board in 1922, which took over the administration of roading from the various roads boards. The toll-gate system in Taranaki was abolished in 1925. Revenue came from various sources of roading taxation. The Highways Board, replaced in 1954 by the National Roads Board, subsidised work on New Plymouth's roads.

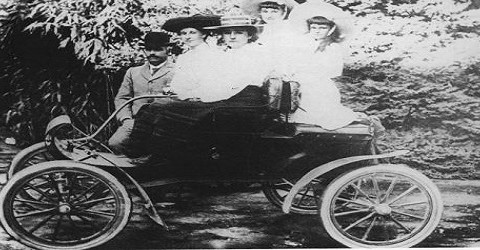

Dr H. B. Leatham, medical superintendent of New Plymouth Hospital from 1898 to 1910, was the owner of the first private petrol-driven car in New Plymouth. It was a single-cylinder Oldsmobile, which he imported in 1902. Previously he had done his rounds on horseback, sometimes using a packhorse. When he bought the car, which had two gears and carried four people, the horses caused as many stoppages as did mechanical troubles. They were terror-stricken by this new-fangled contraption and Dr Leatham,

no doubt worried that his already heavy medical workload might be increased by injuries from his passage, usually waited until the frisky animals could be led away before he drove on. The car was steered by a tiller, ignition was supplied by a dry battery, and for night driving it was equipped with kerosene lamps, later adapted to use carbide. No mechanic himself, the doctor insisted that one of his passengers on out-of-town trips would be the only man in the town who knew anything about cars, J. Rollo, who later started perhaps the first 'garage' in the town. Miss Constance Leatham, the doctor's daughter, who died in 1979, recorded in her diary: 'To make the benzine run better we often used to go up the hills backwards which seemed to do the trick .. Father would take us for drives on Sunday afternoons when the weather was fine, but the roads were not very good and it was not always comfortable. Once we lost a passenger-she had been tossed overboard at the foot of Standish Hill .By 1907 cars were becoming almost commonplace in the town. When the third Waiwakaiho bridge was opened in that year a De Dion car led the procession of ox-carts, horse-drawn wagons, two bicycles and several hundred pedestrians over it. Dr Leatham had by this time replaced his first car with a more up-to-date model, and he continued to take an interest in this 'new' mode of transport. When the Taranaki Automobile Association was formed in 1924 with a membership of 25, Dr Leatham was made its patron. By the late 1970s the association had more than 13,000 subscribing members. Until 1960, when the present premises in Powderham Street were opened, business was transacted in the offices of accountants, Duff and Wynyard, in Currie Street, and later in the Hotel Cargill building in Gill Street. The average motorist trying to find a place to stop on late shopping Friday evenings may not agree, but traffic experts maintain that New Plymouth has never had a parking problem, compared with that in larger cities.

Nevertheless motor cars were causing concern in the town as long ago as 1918 when the borough council decided private cars could only be parked in the borough on the north side of Ariki and King Streets and on the south side of Courtenay Street all Vehicles must be kept parallel with the kerb line as close as possible; a space of not less than five feet to be left between cars; cars not to be placed opposite entrances to buildings or crossings into private property.' Council traffic inspectors used private cars until 1947 when the first traffic control car, a Ford Coupe, equipped with a loud hailer, was bought. Two years later traffic control was handed over to the Ministry of Transport (then the Transport Department) and uniformed traffic officers appeared. Four officers were on the initial establishment under the command of Chief Inspector Tony Anthony, and as traffic flow and population increased, so did the number of administrative and enforcement officers, until in 1979 a total staff of 20 included 12 traffic officers, two meter maids and one senior traffic sergeant. The fleet of vehicles has grown from two cars and a motor-cycle in 1948 to four cars and eight motor-cycles, all stationed in the city. A traffic officer's lot is not always a happy one. Many motorists regard him with annoyance and even hostility. Assaults have occurred, and in 1977 one New Plymouth officer died of injuries inflicted during the course of duty, a case which aroused widespread horror. There is no doubt, however, that enforcement officers are necessary, as has been proved over the years by accident-promoting offences. In common with the rest of New Zealand, accident figures in New Plymouth in the 1970s showed a frightful picture of drunken driving. In March 1974 the senior officer, J. H. Mahoney, reported to the city council that of 27 blood alcohol breaches that month, 14 involved accidents, some of which resulted in serious injury. The problem was increasing, he said, 'and the frightening thing is that so far we don't have any idea of the actual number of people who are driving while intoxicated in the city.' Until 1972 it was not uncommon for traffic officers to control manually the more dangerous intersections. With the introduction of automatic signals the traffic flow increased and the accident rate dropped. The introduction of the Mall in Devon Street in 1976 meant the only major east-west traffic route through the city was no longer available, but advantages far outweighed disadvantages. There was more parking space available, fewer heavy vehicles, a 70% reduction in injury accidents, and a more civilised atmosphere for shoppers. The opening of the one-way pair system-Powderham and Vivian Streets-in the same year brought further improvement in traffic flow. This had its initial problems; there was an increase in intersection

accidents, but gradually the new traffic pattern improved and the system proved its worth. Parking meters were introduced amid much controversy in 1956 when 210 were installed. They paid for themselves in the first year of operation. One of the earliest offenders was the Mayor, E. O. E. Hill, who insisted on being treated like everyone else. Unlike many later offenders he was let off the charge with a warning. Income from meters in 1978 totalled $104,471, which included $81,462 in meter fees and $10,262 in fines.

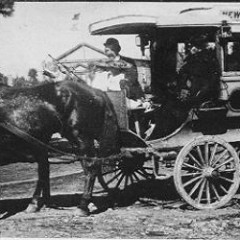

For the first 70 years of its existence New Plymouth's public transport was confined to privately-owned wagonettes, carts and cabs (for which the hire, as laid down by the council's bylaws, was 50c an hour if drawn by two horses, and 40c if only one horse was used). William Page had introduced his one-horse 'public transport system' in the late 1880s, which consisted of a cart, across which were placed planks on which eight passengers could sit for the ride between Fitzroy and the town centre. But as early as October 23, 1900, electric tramcars· were running in Dunedin. The Auckland electric tramways were begun in 1902, and most other large centres had a similar system with a few years. Probably because New Plymouth already had its own small thermal power station the council changed its mind. In 1909 a tramway committee was formed and in the following year Mayor Gustave Tisch suggested a tramway rating area. A report from Frederick Black, the council's consulting engineer, recommended a tramway system be favourable considered, but be postponed until the Greater New Plymouth scheme became a reality. A revised report by Black gave 'a general comparison between the overhead electric tramways, trackless trolley tramways, and the motor- bus undertakings, and I am strongly of the opinion that while in first cost the overhead system is the most expensive of the three systems, it is the cheapest in working costs, the most efficient as a tramways agency, and in regard to the safety of passengers, as well as road users, it is far superior to any system of independent vehicles' .13 The council accepted the recommendation. A poll taken in March, 1913, on the question of raising $110,000 to install the system from the Waiwakaiho to the port, with a branch at Morley Street, was over- whelmingly supported, plans were drawn up and tenders called. But there was a war on, and because vital parts and equipment were delayed, construction was held up. The horse-buses continued, in spite of difficulties while the tramlines were being laid, until that service was abandoned with the opening of the tramways. Horse-bus owner Jones then advertised a different transport service by motor bus. But because of 'no responsibility will be taken for delays through blow-outs or other motor troubles' envisaged by Jones, it was several years before a bus service could compete with tramways.

A new and strange vehicle joined the transport service in 1911-a 22-seat Walker Edison battery bus. Described as a 'slow mover and rather comfortless on its hard rubber tyres', it later became a de- partmental service wagon. Three other battery buses were introduced without finding favour from passengers and were later put to more mundane purposes, one as a faults-truck by the council's electricity undertaking, one as a rubbish collection vehicle, and one which ended its days as a clubhouse at the Fitzroy golf course before a pavilion was built. On Friday, March 10, 1916, New Plymouth became the smallest municipality in the world to run an overhead tramway system. Six trams, made by Boon Brothers of Christchurch, were in operation, painted in 'tasteful red and cream', and as Mayoress Mrs Burgess ceremonially drove the first tram out of the tram barn at Fitzroy to break a ribbon, it was the' culmination of a great dream' .14 In the first week of operation the dream seemed to be coming true, for 18,213 passengers were carried (the town's population was about 8000) producing $24,283 in revenue. Although the novelty wore off, the service continued to be appreciated. In the first year of operation 1,257,804 passengers were carried and F. T. Bellringer, the town clerk, was moved to report: 'The running of the cars has given an air of briskness to the town, due principally to the great number of people who now come in frequently from the suburbs, and who, prior to the installation, owing to the difficulty of transport, only came in at long intervals.' 15 The tramways met a crisis in 1918 when for several days during the virulent influenza epidemic the Fitzroy-Port service was limited to one tram and the Morley Street service was cut out altogether. Following the first World War the town's bus services were rapidly developed. Competing with the trams, the first petrol driven bus was introduced in 1920. In 1923 a tram service to Westown was opened. The fleet then comprised 10 cars, and no further trams were ordered. Three ofthe new trams on the Westown run were Birney Safety Cars, imported from Philadelphia. These were designed for one-man opera- tion, with no conductors, and their main feature was safety, which included a 'dead man control' for use in case the motorman collapsed. Gordon Coates, Minister of Transport, visited New Plymouth to take a first-hand look at the new cars, which were the first to be used in the country. On a test run the driver was asked to test the 'dead man's control'. With the tram moving at top speed he removed his hand from the controls and the tram stopped dead. When the Minister and the rest of the tram's passengers picked themselves off the floor they could do nothing but agree that the dead man's control was effective. Fortunately there is no record of it having to be used in earnest.