3:3

and maintenance of such a stately home was out of the question. Its demolition was attended by sorrowful crowds, the more affluent of whom bought windows, doors and much of the fine timber for a few pence. All that remains in Brooklands Park is a memorial plaque, near the main entrance, to Newton King, and, the huge base of the original fireplace, a relic of Captain King's tenure. A contemporary of Newton King was Chew Chong. Much has been recorded of this Chinese merchant's role in establishing the Taranaki dairy industry, but little of his versatility in other spheres. His descendants, one of whom is Brian Chong, a prominent New Plymouth architect, have in their possession documents and records concerning this remarkable man, some of which have never been published.

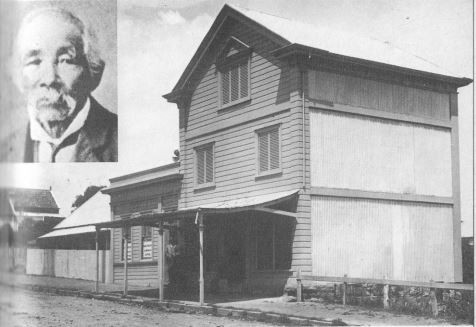

Chew Chong was born in China in 1830. He attended school there and worked for 10 years as a household servant before emigrating to Victoria, Australia, where he spent II years in the goldfields, mining and storekeeping. He joined the gold rush to Otago in 1866; then travelled New Zealand buying up old metal for export to China. During these journeys Chong discovered an edible fungus* which was growing on logs which covered the burned-off timber lands. He found it was similar in taste to a highly prized Chinese delicacy which was also valued for its medicinal value. He offered to buy all he could be supplied with, at 2c for 500 grams. He opened a store on the corner of Currie and Devon Streets in 1870.

The fungus was collected by Maoris and farmers, who brought it into New Plymouth on market days (Saturdays) when as much as $140 worth a day was bought. It was dried and packed into flax baskets, sent to Dunedin and shipped to China.

Between 1872 and 1882 more than 1700 tonnes of this 'Chinese Wool' was exported, to a value of more than $150,000. The sale of the fungus saved many Taranaki dairy farmers, for they bartered their butter to their local store in exchange for goods, and the fungus was their only source of ready cash, apart from labouring in the bush and on the roads. A year after Chong had opened his dairy factory at Eltham in 1887, he turned his attention to meat. He established a butcher's shop in Devon Street East, New Plymouth, installing Sam Hall as manager. His prices were well below those of other butchers, which led to some hostility. But he was, for all that, a respected figure in New Plymouth. 'Dressed in white tussore trousers and dust coat of the same material, he would drive through Devon Street in his phaeton, drawn by a pair of chestnut horses .

Another Chong enterprise was in the art field. He advertised regularly in the Taranaki Herald: 'Persons desirous of having portraits in oil will please let me have their photographs where I can have them sent to China. Prices very reasonable.' These paintings are now heirlooms in s .veral Taranaki family houses. He retired from business in 1905 following a visit to China. Shortly b 'fore his death in New Plymouth on October 7, 1920, at his home in Courtenay Street, he was presented with an illuminated address 'in uppreciation for the enterprise he has shown as a pioneer of the dairy industry', which has flourished to become Taranaki's major export. Real and lasting diversification of New Zealand farm production was made possible by the introduction of refrigeration. In 1882 the Dunedin .arrived the first refrigerated cargo of mutton from Port Chalmers to London.

This meant the country was no longer restricted to Australia as a market for its butter and cheese, sent in brine-soaked casks. Meat too could be exported, as well as sold to the butcher. Indeed, it was in the frozen meat trade that most progress was made in the first decade of refrigeration, the freshly-killed carcasses being taken to the ports and frozen aboard the ships.

As the British demand for butter and cheese increased it was realised a refrigerated bulk storage depot was needed to hold supplies until shipping was available, and in 1895 a private concern, the Taranaki freezing Works Company Limited, was established near Port Taranaki, 'with all the latest and most improved machinery', according to its first annual report. Within five years it had established itself firmly enough to impress the province's various dairy companies, and to make an offer to t hem of $30,527, as a going concern.

This was accepted and the present Taranaki Producers' Freezing Company Limited was formed on May I ,1901 In that year it handled 176,210 boxes of butter and 9530 cases of cheese.

In 1904 the original works was burnt down. Five months later, at a cost of $13,014, a new building was erected and in subsequent years further development took place, until in 1979 the firm's capital value was $8 million, its storage capacity was 29,000 tonnes (filled twice a season); it employed a staff of more than 100, and exports were valued at more than $100 million. Another New Plymouth firm which has had a close association with the farming industry since the turn of the century is MacEwan's Machinery Ltd. It was founded by James Ballantyne MacEwan in Wellington, and a branch office was opened in the town in 1906. Although the firm now deals in home appliances, electrical goods and reneral farm machinery, it was in the dairy field that its reputation was founded.MacEwan, a Canadian, was a dairy expert before he arrived in New Zealand to take up a post as Dairy Commissioner in 1894.

He had received his instruction in the Canadian Experimental Dairy Schools; and in a similar capacity in New Zealand he promoted dairy schools throughout the country, educating factory managers in production of butter and cheese. After two years' service with the Government he pened a small business in Dunedin, and in 1896 moved to Wellington

where he founded J. B. MacEwanand Co. Ltd, specialising in dairy factory machinery. The firm was the first in the New Zealand market in 1908 with proprietary milking machine agencies, although the first milking machine to be seen in Taranaki' had its trial run in a small shed on a farm at Veale Road on Sunday afternoon' in January 1902 It was driven by an oil engine, and for the trial 'an obstinate old cow and very hard to milk' was selected. Although as new to the machine as were most of the spectators, she never lifted a foot and was pronounced 'milk clean' by her owner. L. D. (Laurie) Hickford (1904-1977) was another prominent figure in the dairy industry. He was a directorofthe National Dairy Association for 25 years (10 years as chairman) and in addition to representing many other farming interests, was elected to the New Zealand Dairy Board in 1961, in which position he was active in directing the nation's marketing policy. He stomped the world at the head of more than 30 trade missions. 'The dairy industry was founded on a British market, and we had no fears. And then the European Economic Community reared its head and today (1978) less than 50 per cent of produce goes to England. We have to find new markets. And it's a battle-from one end of the world to another. Once the sun never set on the British Empire; now the sun never sets on New Zealand's dairy produce. But it will unless we continue to fight for that end.'8 But it was in local government that Hickfords influence in Taranaki was most notable. For 41 years he was a memberofthe Taranaki County Council; 27 of them as chairman, during which time he did much to iron out the many problems which existed between urban and rural interests. 'Ever since 1876, when provinces were abolished and county and town councils replaced them, there has been a measure of antagonism between the New Plymouth Council and the Taranaki County Council ... both councils have their own interests at heart and in the past we have had amicable and not so amicable discussions . .. the cost of local government bears more heavily on urban areas than rural districts, and this has widened the differences between the two ... '9 When in 1876 the Taranaki County was delineated, New Plymouth was developing as a market town and administrative centre for the surround- ing farming community, as well as becoming the transport terminus for the region. Indeed, it was roading which occupied the major energies of the newly formed Taranaki County Council, and for many years county councils were considered almost solely as roading authorities. At its first m~eting on January 4, 1877, held in the Provincial Chambers in New Plymouth, Colonel Robert Trimble presided over eight elected members responsible for an area embracing the present Inglewood, Clifton and parts of Egmont, Stratford and Whangamomona counties The trials of the land wars were over, and settlers were combining farming with saw-milling, thereby clearing the forested lowlands. Access was a problem and for many years wheeled traffic to outlying properties was unknown. Loans, rating and tollgates were used to finance the formation and metalling of roads, but it was slow progress for Taranaki, 'the Cinderella of the Provinces'.

The scene changed dramatically in the 1870s and early 1880s. The first railway line had been laid between Waitara and New Plymouth; later Wellington was linked by rail. The Mountain Road (now the Main South Road) made access to New Plymouth relatively easy for farming settlers. A start was made on developing the port at Ngamotu. But it was the advent of refrigeration which gave the greatest impetus to land clearing, and turned Taranaki into one of the country's most prosperous provinces. Until then settlers had farmed on subsistence lines, bartering their produce for supplies from the town's storekeepers. By the end of the 1880s most of the lowlands had been opened up, though until well into the early years of this century blackened tree stumps remained as gaunt testimony to man's eagerness to fell virgin forests. But ash from the burnt bush did enhance the fertility of the soil and for more than 20 years the Taranaki farmer was relatively untroubled by the growth of weeds or pasture reversion. Dairy factories mushroomed. By the turn of the century there were 95 butter factories and 21 cheese factories.

The development of the milking machine enabled the farmer to run larger herds. More milk could be delivered to factories, and this meant better roads were needed. Bridging was a problem and the Taranaki County Council's minute books reveal that most of its activities were centred round raising money to build them and, once built, to keep them in repair. In 1895 the council advertised in the two newspapers that 'the whole of the bridges in the county are in a dangerous state'. In the same year 'Mr W. Julian waited on the council and requested compensation for loss sustained through an accident that had happened to his team falling through the Kaihihi Bridge'. He was driving a wagon with a five-horse learn and had 'two tons 5 cwt' aboard. He was 'willing to accept fifty pounds for damage'. The bridge was rebuilt, but there is no record of Mr Julian having received compensation. A notice was placed on the Tapuae Bridge notifying 'that persons must not ride or drive over it beyond a walking pace'. And 'The settlers at Okato guaranteed forty pounds ($80) towards the cost of erecting a new bridge.' They were still having trouble in 1897. A bylaw dealing with traffic was enacted, under which it was illegal for heavy traffic of all kinds to be used on 'all county roads within the county of Taranaki' during the months of May, June, July, August