8:2

This was used for purposes other than worship. In 1842 it was the venue for a public meeting called by Charles Armitage Brown (father of Superintendent Brown) to debate 'removing the town to a place where a harbour can be procured'. A memorial to the New Zealand Company was outspoken: Colonel Wakefield was to be informed of the settlers' 'ruinous situation in consequence of the Company not fulfilling their agreement by placing them on part of the island on a coast where it is impossible for any vessel to anchor with safety. There was talk of suing the company, but Carrington stood firm on his view that it was better to have a settlement on good land where there was no harbour than on a harbour where there was no good land. Other demands for the little church soon brought a different crisis. When the churchmen declined an application for a horticultural show, the hand of authority descended. Captain King and the company's agent, Wicksteed, ordered the removal of the building. They had legal authority, for the chapel had been built before Carrington's survey had been completed, and it encroached on a public road. The Wesleyans in 1849 bought from the Congregational Church an uncompleted building on the corner of Courtenay and Liardet Streets. This had been started by the Horatio Groube of the Congregationalists who had arrived in February 1842 and who had striven without success for 19 years to build up his denomination. It was a sandstone chapel. Groube was unable to complete it for lack of funds. It was on the site of the present Whiteley Memorial Church, first built in 1898 and com- pletely rebuilt in the 1960s. Side by side-and indeed in the early days often overshadowing similar work amongst the Europeans-the Methodist Maori missions were conducted, and the most notable of the missionaries, John Whiteley, joined 'the noble army of martyres' while in charge of the New Plymouth church and mission. Whiteley was born in Notting- hamshire in 1806, ordained in 1832 and arrived in New Zealand the following year. Stationed at Kawhia and later at Pakanae, he under- took many missionary journeys, mostly on foot, and was influential in persuading the Waikatos to free their Atiawa slaves. He was president of the Auckland Methodist District and in 1856 moved to New Plymouth where, besides his mission work, he did much to smooth ruffled feelings between Maori and Pakeha. Whiteley had charge of the Grey Institute; he was also an unsalaried Native Land Commissioner, and through his fluency in Maori acquired great mana among the various tribes. <br.

On February 13, 1869, he rode out to visit the military settlers at White Cliffs, north of Waitara, but, ignorant of the fact that they had been massacred earlier in the day by Hone Wetere's war party, he was ambushed and killed. Whiteley is commemorated by the Whiteley Memorial Church, by a cairn near where he fell, which was unveiled in 1923, and by a stone obelisk in Te Henui Cemetery. The Primitive Methodist movement flourished in New Plymouth a century ago and its minister, Robert Ward, became a prominent figure in the community. Many of the early settlers, who came from North Devon and Cornwall, were members of the Bible Christian Society. Among them were several local preachers who, feeling in need ofaleader, wrote to the officers of their movement in Devon, asking that a 'travelling preacher' should be sent to them. The founder of the society was William Bryan of Cornwall who had left the Wesleyan movement to found the 'Bryanites' which, although independent, adopted the principles of Methodism. Shortly after the establishment of New Plymouth a small chapel was built in the centre of the little township. Wells, in The History of Taranaki, records: 'On a Sunday afternoon (September 1, 1844), when the afternoon service had concluded in their little chapel, they observed a stranger standing on a chair preaching on the Huatoki bridge. Mingling with his congregation they soon perceived that the strange preacher taught doctrines in accord with their own religious principles.' The preacher proved to be Ward, a missionary sent out by the Primitive Methodist Society who had just arrived by the ship Raymond from London. The result was that Ward became their minister, a position he occupied until moving to Wellington in 1865.

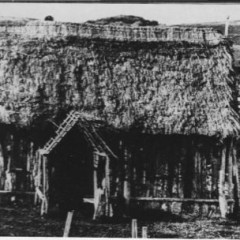

The Primitive Methodists, the Free Methodists, the Bible Christian Church and the Wesleyan Methodist Church became united in 1913. Perhaps the oldest stone church still standing in New Zealand, St Mary's in Vivian Street, was opened in 1846. Previous to this Anglicans had worshipped in the Methodist Church, but when Bishop Selwyn visited the settlement in 1842 and found that 61% of the settlers were of the Anglican faith, he selected the site which was then a 'Maori garden and bush which extended to the top of Pukaka or Marsland Hill' . He was also instrumental in sending the first Church of England clergyman, William Bolland, who arrived in 1843 to find no church to work in. Services were held in a building in Currie Lane not far from the present Taranaki Newspapers building. It was little more than a raupo shed, but served the congregation for six months before it was blown down in a gale. While waiting for St Mary's to be built the congregation moved to the courthouse on Mt Eliot. Bishop Selwyn gave Bolland the choice of buying a cottage belonging to Captain J. G. Cooke or having a new house built near the church. Bolland chose the former which consisted of two

wings separated by a passage. Between these wings, according to the journal of Selwyn's chaplain, the Rev. William Charles Cotton 13 a granite building was erected in 1844. This' Stone Vicarage' was bought by the City Council in 1946, and has been restored by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust. The foundation stone of St Mary's was laid on March 25, 1845, but before the building was completed a year later there was evidence of opposition so typical of the period to the project by other denomina- tions. There was one feature of the building to which the Methodists, and indeed, many Anglicans, reacted in something approaching anger: the credence table which is, in effect, a sideboard near the wall on the south side of the altar on which the objects needed for communion are placed. In his diary in December, 1845, the Methodist minister, Hanson Turton, wrote: 'A stone "credence" table having been built into the wall of the episcopalian Church now in process of erection, a meeting was held this day at which the subject came up for discussion, when the minister actually told his people that it was built at the order of his Bishop (Dr Selwyn) and endeavoured to smooth it over by remarking that "as he was rather awkward about the feet it was simply intended to be a more convenient situation on which to place the sacramental emblems than either the floor or the pulpit steps" . If they can swallow that they may gorge anything. My own opinion is that it is a mere Camden "feeler," only to be succeeded by all the etceteras of the sect; and if the people will only sit still, though popery be peeping in from the wall, it will soon to be observed stalking triumphant in the chancel. It will doubtless, however, be a stone of offence, in future years, to all episcopalian emigrants who may have seen Puseyism at work at home, and already one clergyman has offered £5 for its removal. The Cambridge Camden Society was active in England at that time, tidying up and restoring neglected churches and providing adequate fitments so that the altar need not be used for everything. High Church clergy revived the Roman Catholic credence table and although it became something of a shibboleth for Low Church adherents, eventu- ally it was pronounced legal. Edward Pusey led the Catholic revival in the Church of England during the 1830s and 1840s. Other evidence of inter-denominational hostility existed William Woon, another Wesleyan missionary stationed in New Plymouth, reported to his headquarters in London: 'All kinds of means have been employed by the Church party to show the superiority of the Episcopate to the Wesleyan Church'.

And, in May, 1846: 'The walls of the Anglican Church building here appear to be rising very slowly, and the "wonder- ful stone" placed in a certain spot, after the Camden Society's plans, is a stone of stumbling to many, and for the sake of the Protestant cause ought to be broken into pieces.' The original credence stone has long since disappeared, as have the hostility and one-upmanship between various denominations during the many alterations and additions which have taken place at St Mary's. But in the 1840s prejudice and exclusiveness were too strong to be broken down, even by shared hardships and privations. Notwithstanding a 'gentleman's agreement' for the Anglicans to concentrate on the east coast of the North Island and the Wesleyans on the west, this was not faithfully observed, and much sorrow and anger was aroused over mutual trespass in Taranaki, notably New Plymouth. The diary of Richard Taylor, the Anglican missionary at Wanganui who celebrated Holy Communion and conducted baptisms in New Plymouth before Bolland was qualified to do so, contains many references to 'poaching'. He resented the fact that sometimes Maori converts whom he had excluded for such sins as adultery, or whose baptisms he had delayed so that they might be properly prepared, had been accepted by the Wesleyans. He recorded in 1847: 'Mr Woongave a morning service which interfered with mine. No singers came.' Ten years later the situation had worsened and there was a note of sadness in Woons journal: 'There is very little doing among the aboriginals at present. They are drunk with money and power ... alas, one of the evils of colonisation. Would that Church and Wesleyan missionaries had the natives under their influence as in time past. Now there are Papists, Socinians, Swedenborgians, Normonites, Plymouth Brethren, etc, etc. Where is the road?' It was many years before the various denominations discovered the road. Meanwhile St Mary's Church was completed. Designed by F. Thatcher, it was built by George Robinson, Thomas Rusden, Harry Hooker and Philip Moon from boulders drawn by horse wagons and bullock carts from the beach. The first service on September 29, 1846, was held without formal dedication because Bishop Selwyn, arriving by ship from Auckland, found the seas too rough to allow him to land. A year later, Bolland, who was then aged 27, and who had never been a robust man, died after three and a half years' service. Bishop Selwyn, who visited the town, said he 'heard such words of unfeigned sorrow and respect from parishioners that I could scarcely hope to hear from a congregation so recently formed under so young a minister' . Bolland was buried in St Mary's churchyard and in addition to his headstone two Mediterranean cypresses were planted near the grave- said to be the first exotic trees planted in New Plymouth. Bolland was succeeded by Henry Govett, who ministered to Anglican needs of the community for half a century, first as vicar and then as the first Archdeacon of Taranaki. He retired as vicar in 1898 and as archdeacon in 1902, one year before his death, and was buried beside his predecessor. The first vicarage was built in 1860 on the site of the present building next to the church. Close by the Vivian Street gate there grows a thorn