The Industrious Heart A History of New Plymouth

by J. S. Tullett

Published by the New Plymouth city council

Contents

1: X Marks the Spot

2: According to Plan

3: Land-lure

4: Big Business

5: Nodding Neddy

6: Ox-carts and Jets

7: Keeping Minds Employed

8: Hear the Word of the Lord

9: A Matter of Life and Death

10: Pass the Word

11: Justice, Rough and Smooth

12: Pursuit of Happiness

13: Play the Game, there!

14: Liberty, Maternity, Fraternity

15: Pubs and Clubs

16: A Risky Business

17: The People's Choice

Foreword

The Industrious Heart is not just another history book published as a centennial project to celebrate 100 years of local government in New Plymouth. It is an exciting and moving story about people. From the days of Dicky Barrett the author traces events and occasions that in effect are stepping stones bearing the footprints of the generations of people who have lived and contributed to the settlement and growth of New Plymouth.

The impact of that remarkable planner Carrington is faithfully recorded and as the chapters outline events from those very early days through the busy years to the exciting development of Maui, one is conscious that this richly endowed city still bears the indelible stamp of Carrington.

The book reveals the basic reasons why as a city we are linked so intimately to the land. I believe the author has exposed the character of New Plymouth and its people and one can sense the growth and change in that character as industry and the Maui development have claimed their place in the city's social and economic structure.

The Industrious Heart is not a book just for the student or the historian. This is a book about people for people and I am sure all who read it will appreciate and enjoy the author's intimate and personal interpretation of historical events and facts. What could easily have been a factual and stolid historical document is in fact a very entertaining and exciting narrative of our city. It is most appropriate that this project should have been approved and initiated during our centennial celebrations. The Industrious Heart continues to beat strongly as we move into another century.

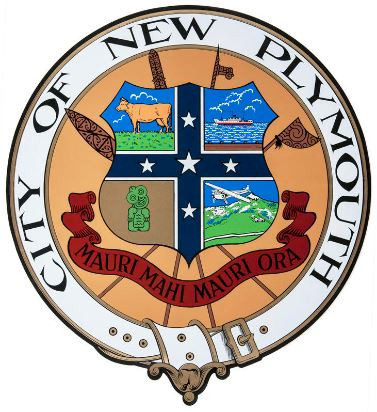

Civic crest

In June, 1941, the New Plymouth Borough Council decided to live up to its motto-' The Industrious Heart Lives' -by making changes to its civic crest, designed in 1898. The steam auxiliary ship in the top right quarter of the emblem was to become' a proud merchant vessel equipped with radio', while a tree fern was to be replaced with an airport scene showing Mt Egmont and the famous monoplane, the Southern Cross.

The crest was first suggested in 1898 by Mr W. F. Gordon, designer of the illumina- tions on Government buildings in New Plymouth for Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee the previous year.<br.

He drafted a design showing the Southern Cross (stars), a milch cow, the breakwater with shipping, a tree fern and a greenstone tiki. Mr Freeth, clerk of the court and an ardent Maori scholar, suggested a motto in Maori which means, 'The industrious heart lives, or survives; the indolent heart dies, or goes under.' The council shortened that to 'Mauri rna hi mauri ora' (,The Industrious Heart Lives').The Maori weapons shown behind the shield are:- Top right: A Ko-a digging implement sometimes used as a weapon of war. Lower right: A Tewhatewha-a weapon of war with quillets of split feathers attached. Top left: A Taiaha-a weapon or staff of rank. Orators carry this 'taiaha' while addressing their people. Lower left: A Hoe-a paddle. Top right quarter: A berthed merchant vessel depicting the development of the port and importance of commerce. Bottom right quarter: New Plymouth airport and the monop- lane Southern Cross. This marks the importance of commercial aviation and associates the area with the pioneer trans-Tasman flights by Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith and Charles Ulm, Top left quarter: A Jersey cow, representative of the dairying interests in the Taranaki province. Bottom left quarter: A Heitiki-the Maori ornament. Hei translates as being a neck ornament and tiki is the form of man. The first piece of the insignia of office of the Mayor of New Plymouth arrived in March, 1938, and was displayed in Whites Ltd's shop window. It was a mayoral chain, described at the time as being 'chaste in design, somewhat of the conventional style of such work'. The central piece showed snow-capped Mt Egmont and the Southern Cross aircraft. Suspended from that was the New Plymouth borough's crest surrounded by flowers of native plants. On the other side of that silverwork was inscribed the charge given to each mayor taking office: 'Fear God, honour the reigning sovereign. Render true and faithful service to the people. Serve New Plymouth with diligence and courage and guard jealously its good reputation.' The chain was the workmanship of Messrs Walker and Hall to a design by the town clerk, Mr F. T. Bellringer.

When a visit by King George and family was announced for 1948 (later cancelled when the king became ill), the New Plymouth municipality was one of the few centres to be without mayoral robes. It was decided to get some-from Britain, of course. These arrived in 1949 and were made of black heavy corded silk material with fine silk lining, and trimmed with imitation white ermine. They were worn officially for the first time six months later when the Mayor, E. R. C. Gilmour, welcomed Miss New Zealand 1949 (Miss Bobbie Woodward) back to her hometown. The mayoral black cocked hat with gold braid arrived in 1953 in time for Queen Elizabeth's visit the following year.

The Maori weapons shown behind the shield are: Top right: A Ko-a digging implement sometimes used as a weapon of war. Lower right: A Tewhatewha-a weapon of war with quillets of split feathers attached. Top left: A Taiaha-a weapon or staff of rank. Orators carry this 'taiaha' while addressing their people. Lower left: A Hoe-a paddle. Top right quarter: A berthed merchant vessel depicting the development of the port and importance of commerce. Bottom right quarter: New Plymouth airport and the monop- lane Southern Cross. This marks the importance of commercial aviation and associates the area with the pioneer trans-Tasman flights by Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith and Charles Ulm, Top left quarter: A Jersey cow, representative of the dairying interests in the Taranaki province. Bottom left quarter: A Heitiki-the Maori ornament. Hei translates as being a neck ornament and tiki is the form of man. The first piece of the insignia of office of the Mayor of New Plymouth arrived in March, 1938, and was displayed in Whites Ltd's shop window. It was a mayoral chain, described at the time as being 'chaste in design, somewhat of the conventional style of such work'. The central piece showed snow-capped Mt Egmont and the Southern Cross aircraft. Suspended from that was the New Plymouth borough's crest surrounded by flowers of native plants. On the other side of that silverwork was inscribed the charge given to each mayor taking office: 'Fear God, honour the reigning sovereign. Render true and faithful service to the people. Serve New Plymouth with diligence and courage and guard jealously its good reputation.' The chain was the workmanship of Messrs Walker and Hall to a design by the town clerk, Mr F. T. Bellringer.

When a visit by King George and family was announced for 1948 (later cancelled when the king became ill), the New Plymouth municipality was one of the few centres to be without mayoral robes. It was decided to get some-from Britain, of course. These arrived in 1949 and were made of black heavy corded silk material with fine silk lining, and trimmed with imitation white ermine. They were worn officially for the first time six months later when the Mayor, E. R. C. Gilmour, welcomed Miss New Zealand 1949 (Miss Bobbie Woodward) back to her hometown. The mayoral black cocked hat with gold braid arrived in 1953 in time for Queen Elizabeth's visit the following year.

Portrait of a Town

Geographically New Plymouth is out on a limb from the rest of the North Island of New Zealand. Because of this it has acquired a character of its own. From the beginning it was dogged by misfortune. Its settlers had bought the land, without knowing what they had paid for, before leaving Devon. They found possession difficult; some found it impossible because of multiple ownership. But it was good land; land which Frederic Alonzo Carrington, the Plymouth Company's surveyor who laid out the town in 1841, described as 'the garden of this country' .1 Before the Europeans came the Maori tribes had battled for it; later they fought the Europeans for it-and lost it; since then it has been land occupied predominantly by Europeans, who made certain they in- tended to keep it.

They were the conquerors, and their attitude to the Maori varied from apathy to open hostility. Indeed, a little more than a century ago the survival of the Maori was hardly a debatable matter 'because it was patently clear that the race was dying. The most charitable thing to do was to smooth the dying pillow and to note with regret that this was the sad but inevitable consequence of an advanced civilisation coming in contact with a noble but primitive race.'2 The race did not die. It flourished in many parts of the country. But in New Plymouth-the seat of the fire which sparked off the 'land wars' of the 1860s-Maoris have been conspicuously few in number-and still are. By the turn of the century there were fewer than 100 Maoris out of a total town population of 4405; in 1926 these figures were 170 out of 11,000; and in 1976 the city's population was 37,711 of whom 1544 were 'full Maori, three-Quarter-caste Maori, half-caste Maori, and Maori-other Polynesian.'3 And so this book is basically a European history of a European settlement. Against the magnificent backdrop of Mount Egmont and its ranges, New Plymouth is built on aseries of ridges, steep-sided and generally running in a northerly direction. Carrington found the vegetation of the area ranged from sand-grasses, fern and scrub, to dense forest. This variation was probably due to the occupation of the area by the Maoris who had over the years pushed back the edge of the forest to obtain land for cultivation. 'The Maori, in preparing land for cultivation, always cleared the bush (not the fernland) which they then only used for one or two seasons. This continual clearing had therefore changed the natural vegetation from dense forest to fern and scrub. When Carrington arrived in 1841 the land had been almost deserted for a decade following terrible battles between Taranaki and Waikato tribes. It was so overgrown that he recorded: 'The country is clothed down to the shore and it is impossible to penetrate any distance from the coast except by a native path or track-you may spend hours to get a mile. It is not a little labour to layout a town in a country where it is impossible to stir without cutting your way." On this foundation New Plymouth has been built; from a collection of raupo and pitsawn timber huts housing fewer than a thousand Euro- peans in 1843, to a city of concrete, glass and steel in 1980 inhabited by almost 40,000. But cities do not spring up spontaneously without reference to their surroundings. 'They grow as the result of a potential demand for the performance of certain functions which can best be carried out in one place.

Specialisation in occupations or economic activities is the social and economic factor which leads to the development of cities a city shorn of its hinterland soon withers New Plymouth's 'hinterland' is now lush pasture, right up to Egrnont's bushline. Half an hour's walk from the city centre in any direction, save along the seashore, brings one into some of the world's most highly-developed farmland. Indeed, environmentalists say it is over-developed: creeks, swamps and marshes have been filled in and bulldozed flat, destroying animal, bird, insect and marine habitat, exploited in the sacred name of production. Pockets of native bush remain; but many fear that these, too, are fighting a losing battle against the march of progress. For more than a century this dairying and hill-country farming has been New Plymouth's raison d'etre . Local, national and international firms supply and service tractors, motor vehicles, farm bikes, insec- ticides, milking machines, and the countless other mechanical aids to modern farming; stock and station agents, furniture shops; supermar- kets, serve farmers' and citizens' family wants.

To the east of the city is a large fertiliser works whose product is so necessary to keep farm production as the country's largest earner of foreign exchange; at the other end, near the port, a huge cool store complex keeps the end product of the farms until shipping is available. The town depends upon the country, and vice-versa. New Plymouth people may be excused for pride in their city. Blessed originally with many potential natural parklands, reserves and domains, these have been cultivated and nurtured to become, like Pukekura Park and the Bowl of Brooklands, internationally famous. Other delightful recreational areas are founded literally upon rubbish.

For the past 60 years the town's scavenging service has deposited the citizens' house- hold waste and street-sweepings in a designated rubbish tip in one of the many gullies in the town. When filled, these have been grassed over, planted with shrubs and developed as sports areas; and new rubbish tips formed in new valleys. This service has been augmented by an annual Clean-Up Week, begun in World War One by the council's first sanitary inspector, R. Day, and subsequently changed to Clean-Up Day, when citizens are invited to deposit anything they regard as waste on the public footpath from where it is collected by council transport. Many thousands oftonnes have thus been collected, and the result is that the city has large public recreational areas, the envy of many larger centres.

Trees are treasured, some are protected by by-law, and the periodic topping of trees in streets where power and telegraph lines have not yet been buried, arouses passions which spill over into the Letters to the Editor columns.

A New Zealand 'tradition' requires individual housing sections, and although in recent decades the building of town houses and flats has increased, there are many people who still regard a house separated from its neighbours by a garden and surrounded by a hedge or fence as a necessity.

This continuing trend has aroused criticism from several quarters. In 1976 the Member of Parliament for New Plymouth, Tony Friedlander, commented: 'I believe the sprawl of the city on to some of our best rural lands is a mistake, and it has been made just within the last few years. This is something I think we will regret in the long run.

There have been other mistakes, the results of which were not envisaged at the time they were made. Carrington saw miles of sandy beaches to the north-east of Ngamotu where he landed through the surf. Forty years later the breakwater was built, and of necessity a railway line along the coast followed, effectively cutting off the town from the seashore and putting paid to dreams of making New Plymouth a seaside resort and 'one of the greatest watering places in the South Pacific'. Over the years an esplanade (now Regina Place), a promenade, a concert hall on a pier 100 metres from the shore' after the manner of halls at Margate, Scarborough and Plymouth in England'" and a marine drive from the port to Fitzroy have been suggested. In each case there was great interest but no action. Only at Ngamotu was the beach and its foreshore utilised, and for many years a fairground atmosphere, with a large pavilion, a miniature railway, bathing, swimming and sailing became popular attractions for thousands of townsfolk and visitors. But with the development of the harbour in the 1960s, entertainment facilities were demolished. Elsewhere the sand has left the beaches, save at Centennial Domain,

which is exposed to the rough weather and is unsuitable for aquatic activities except on very calm days. Perhaps because it is a place apart from more progressive centres, the violence and crime which has plagued the rest of the country in recent years has to a large extent by-passed New Plymouth, although it has had its share of drug prosecutions and domestic violence. There has been comparatively little industrial trouble; what strikes there have been are part of national movements. The people look after their own. Local body and school committee elections are invariably contested, sometimes heatedly; churches are well patronised; the plight of the handicapped, the elderly and the needy and appeals by charitable organisations are seldom ignored. Perhaps this is because New Plymouth is small enough to be able to see such needs in its midst. The people's conservatism and spirit of independence stems from their parents and grandparents, who worked and played hard to better their own and their children's lot. A newcomer to the town, unless he or she has the necessary social and financial background, may find it difficult to be 'accepted'; he has to prove his worth before he is admitted to whatever circle he aims for. Because of this there has been criticism, when words like clannishness, insularity, unfriendliness, even snobbery are used. This is not new for New Plymouth. There has always been class distinction; most of it unjustified. The Richmond and Atkinson families, who played such a vital role in New Plymouth life in the early time of settlement, were well qualified to judge their fellow men. Both families were 'educated and cultured; a unique group of middle-class English men and women', but they were without doubt among the highest 'class' to live in the town. In July 1853 Jane Maria Richmond, in one of her many letters describing events in the settlement, wrote of the campaign in which James Brown was elected superintendent of the province: ' ... Mr Pheney, a former law stationer, is a sensible little man; but as he is known to be in his heart a member of the liberal and Brown faction, his impartiality and willingness to let all sides be heard is not satisfactory to the "snobocracy" as Jas (James Richmond) calls the genteel of this place. But they I believe call the Brown party "the Snobs".'9 Many famous visitors to this country have claimed authorship of the phrase: 'I called on New Zealand at the weekend. It was closed.' And it is a fact that the Industrious Heart of Taranaki is almost lifeless from Friday night to Monday morning. The city's bus service runs a skeleton, often empty, service to and from the suburbs where citizens' energies are diverted from work in the factory and the office to perhaps even harder work in the garden or up on the roof. New Plymouth people are proud of their homes, and the streets where they live: entries for the annual Street of the Year competition prove this.

On Fridays the life-tempo in the city changes. The farmer has always brought his family into town on 'market day' for late-night shopping, and footpath congestion in Devon Street has been a problem for most of this century as old friendships are renewed and new ones made. This has not been because the crowds are so great or the pavements too narrow, but because town and country people seem to have a liking for a bit of gossip. In 1920 the borough inspector was publicly criticised for failing to break up footpath gossiping. A by-law was introduced compelling people to keep to the right; later this rule was changed to make people keep to the left-and a white line was painted on the footpath to help them do it! To no avail: the inspector reported that any attempt to discipline Devon Street gossipers was futile. Visitors were often told that Devon Street was the longest straight street in the Southern Hemisphere-more than four kilometres without a bend. In 1979 the establishment of the Mall and a one-way system prevented motorised traffic from using the full length; but the pavements were still a Friday night attraction. The Mall was one of many contentious issues discussed at great length in every forum, but when it became a reality it was accepted by all concerned. By and large the residents of New Plymouth have had little cause to resent the way they are governed, and when crises arise and decisions have to be made-such as moving the railway line from the centre of the town in 1907; demolishing the clock-tower in 1968; the method of sewage disposal in 1980--the council' s record shows that it abides by the majority decision. When the town was declared a borough in 1876 the first mayor was a prominent lawyer, and his councillors were leading professional and business men. This pattern was followed roughly until after World War Two when tradesmen-and later women-were among the people's choice. At first the mayor and nine councillors conducted the town's affairs. By the turn of the century there were 12. In 1916 this was reduced to eight, a situation which satisfied the electors until 1950 when it was felt that increasing work required ten. In 1980 the mayor and 13 councillors ruled the city. From its inauguration in 1876 the structure oflocal government in New Zealand, including Taranaki, has been the cause of much dissatisfaction, primarily because of the proliferation of local authorities of all types. Many parliamentary investigations confirmed the necessity of consoli- dation, and various moves towards reform have been made. The latest was in 1979 when the Taranaki United Council was formed, with representatives from 17 local bodies, three from the New Plymouth City Council. Its statutory obligation was to undertake the functions of civil defence and regional planning. The united council came at an opportune time. On the national front the country was facing the worst unemploy- ment problem for fifty years and inflation was getting almost out of hand. New Plymouth shared in both these problems.

Taranaki's greatest resource has always been the products of its farmland-and, since Kapuni, and Maui-its oil and natural gas; valuable commodities in anyone's language. And when, in 1980, the Government decided to place multi-million dollar fuel processing plants within 20 kilometres of the city, there was, in spite offears of possible pollution and an upsetting of the city's lifestyle, a new spirit of hopefulness for benefits which such an undertaking could bring. The united council devoted much effort to planning to protect and utilise this new source of wealth to the fullest potential. More than one public speaker referred to 'devolution', and hinted at secession. Should Taranaki go it alone? It had almost everything necessary for indepen- dence, and could drive for most favourable deals in any trade bargain- ing-an economic base of which many another district would have been envious. Their arguments were perhaps specious; but were listened to attentively. After all, there was a precedent-and in Taranaki. In 1879 Hawera formed itself into a republic and set up its own volunteer regiments because the central Government could notor would not protect it from feared destruction as a result of Te Whiti's campaign against alienation of Maori lands. 1 0 Why, it was argued acentury later, should not New Plymouth and the rest of Taranaki use a similar device to safeguard its resources against those who would seek to make undue profits from them? The 'Republic of Haw era' was, of course , apolitical extravaganza; but it served its purpose and when it dissolved itself after two and a half weeks, GovernorGrey senta telegram of congratulation to all concerned!

This is the background to this history. Such books can never be the work of one person. This one is the result of countless interviews; letters to people in various parts of New Zealand and in other countries, literally hundreds of telephone calls, chance meetings on the street, calls on individuals, firms, private and public organisations, societies, associations and clubs, most of whom have done their utmost to supply information. Special thanks must go to A. B. Scanlan and H. D. Mullon, New Plymouth historians, who gave permission to use much of their published work; to the late H. A. H. Insull whose family papers and the press cuttings collected and indexed by his late father, H. W. Insull, are now housed in the Taranaki Museum; to the editors of the Taranaki Herald, the Taranaki Daily News and the Sunday Express; to the city librarian Anne Shipherd; to the Taranaki Museum director Ron Lambert; to the staffofthe Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington; toJune Litman, who helped prepare the manuscript for publication and to Murray Moorhead who read and corrected the proofs. New Plymouth has not been short of historians, as the bibliography (Appendix H) demonstrates. The source of much of the information here has been these books and documents, mainly only as a reference unless some previously unpublished material has been uncovered.

This book is divided into 17 chapters, each one dealing with one facet of a century or more of life in a growing town. Because of this there must be some repetition of names and dates because most people are connected with more than one activity. When decimal currency was introduced on July 10, 1967, with the dollar as the monetary unit, the pounds-shillings-and-pence era van- ished overnight. For many older people it took some time to become familiar with the new system, but today the pound sterling has little relevance. Values are continually changing: in 1900, for instance, a pound would be worth much more than its 1980 equivalent of two dollars, and comparisons of values could be difficult and perhaps confusing. It was therefore decided, in the interests of simplicity, to convert all prices, except where they are used in direct quotations, into decimal currency. Similarly miles, yards, inches and acres are now history and the metric system has been used. Thomas Carlyle called history a distillation of rumour. Distillation is a complicated process and this history may contain errors of fact. Readers are invited to send documented corrections for notation in a master copy of The Industrious Heart deposited for this purpose in the New Plymouth Public Library. In 1976 the New Plymouth Historical Publication Committee was formed by the City Council to supervise the production of The Industrious Heart. It comprised Councillors B. S. E. Bellringer (chairman), Audrey Gale, Muriel Livingston and R. J. Burkitt, with Anne Shipherd, Ron Lambert, Murray Moorhead (representing the Taranaki Branch of the New Zealand Historic Places Trust), and Kinsley Sampson, the town clerk, as secretary, all of whom read the draft manuscript and made helpful suggestions. Elizabeth Lynch, of the library staff, and two students, Lynda Ball and Tim Moriarty, worked for a time on research of various aspects of the book. John Tullett was responsible for the chapter heading graphics and for the overall design of the book. The completed volume was to present a history, not just of a municipal government's activities, but of all European settlement and development of the town from 1840. To do this justice it should include a brief outline of pre-European events. It was to be up-to-date-which meant, in most cases, 1980. Size was stipulated at about 200,000 words; there should be about 120 photographs; time limit for research and writing was set at four years. Finally, it should be a 'serious' work, but should also appeal to the 'average' reader. If The Industrious Heart fulfils these criteria it will have satisfied its originators. If it stimulates the reader to delve further-there is still much to be told-it will have served the purpose for which it was written.